User:Kuon.Haku/沙盒

| |

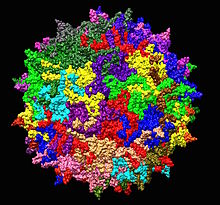

| 一种用作人基因治疗载体的腺相关病毒1LP3的3D原子结构 | |

| 科学分类 | |

| (未分级): | 病毒 Virus |

| 域: | 單鏈DNA病毒域 Monodnaviria |

| 界: | 称德病毒界 Shotokuvirae |

| 门: | 科薩特病毒門 Cossaviricota |

| 纲: | 第五病毒綱 Quintoviricetes |

| 目: | 小病毒目 Piccovirales |

| 科: | 细小病毒科 Parvoviridae |

| 亚科: | 細小病毒亞科 Parvovirinae |

| 属: | 依赖性细小病毒属 Dependoparvovirus |

| 包括 | |

| |

腺相关病毒(Adeno-associated viruses,常缩写为AAV),是一种隶属细小病毒科依赖性细小病毒属、能够感染人类以及其他部分灵长类动物的病毒。腺相关病毒直径约20纳米、无被膜,无法自主完成复制,全基因组长约4.8千碱基对(kb)[1][2]。

目前,尚无已知的疾病与腺相关病毒有关。腺相关病毒一般只能引发轻度的免疫反应。加之腺相关病毒无法自主完成复制等原因,使研究者认为腺相关病毒适合用于改造用作人基因治疗的载体,以及体外等基因人类疾病模型的构建[3]。由腺病毒改造而成的基因治疗载体能够同时感染分裂中和分裂不活跃的细胞,并将载体DNA以一种不整合入染色体的方式导入到细胞中(不过在自然条件下,也有腺相关病毒携带的DNA在感染后插入染色体的报导)[4]。目前,一部分使用腺相关病毒的基因治疗临床试验取得了正面的结果[5]。

历史

编辑腺相关病毒最初被认为是腺病毒制备过程中混入的污染物之一。20世纪60年代,匹兹堡大学的鲍勃·艾奇逊(Bob Atchison)与美国国立卫生研究院的华莱士·罗(Wallace P. Rowe)实验室的工作最初确定腺相关病毒是一种依赖性细小病毒。后来的血清学研究表明,腺相关病毒不能造成任何已知的人类疾病,且只能在腺病毒、疱疹病毒等辅助病毒存在的前提下才能感染人类[6]。

生命周期

编辑虽然存在腺相关病毒能够在没有辅助病毒存在的前提下完成裂解细胞的过程,但绝大部分情况下,腺相关病毒需要辅助病毒的存在才能完成完整的生命周期[7]。腺相关病毒在感染细胞后,需要辅助病毒的帮助(例如,腺相关病毒的辅助病毒疱疹病毒能为其提供DNA聚合酶和解旋酶以及一些对腺相关病毒转录的早期启动必要的蛋白)才能进入裂解期,进行病毒复制。在没有辅助病毒的前提下,腺相关病毒基因的表达将会受限,一部分腺相关病毒DNA会在这种情况下插入至人19号染色体q13.4区域,即AAVS1位点[8]。

基因组

编辑腺相关病毒的基因组由一条长约4.8千碱基对(kb)的单链DNA构成,有的情况下这条DNA是正义链,有的情况下这条DNA则是反义链。腺相关病毒基因组两端是一对长145碱基对(bp)、序列对称的反向重复序列(ITR)。这对反向重复序列对腺相关病毒的复制[9]、衣壳化[10]、以及插入宿主染色体的过程有重要作用[11][12]。腺相关病毒基因组的中间部分含有两个开放读框rep与cap。其中,rep读框上同时存在p5、p19,以及p40三种启动子序列。p5与p19启动子与rep读框编码的Rep蛋白转录相关,分别控制Rep蛋白的两种转录本表达。这两种Rep蛋白的转录本各含有一个内含子,根据转录本的类型以及内含子的剪切与否,Rep蛋白存在四种变体:Rep78、Rep68、Rep52,以及Rep40(Rep后面的数字代表这种蛋白的分子量为多少千道尔顿)。而p40启动子则控制cap读框编码VP1、VP2,以及VP3三种蛋白的表达。VP1、VP2,以及VP3蛋白的编码区域存在部分重叠[13]。此外,一种腺相关病毒的非结构蛋白AAP编码域也位于cap读框中[14]。

用于基因治疗的潜力

编辑腺相关病毒因毒性低、不能自主复制、不致病,且较少整合到宿主基因组中,而被认为是一种较为理想的基因治疗载体。将腺相关病毒改造为基因治疗载体的具体操作方法是,将腺相关病毒基因组上的rep与cap区域替换为目的基因[3][15]。腺相关病毒载体导入人体后,不分裂的细胞能够一直保持输入的目的基因片段,而持续分裂细胞则会逐渐随细胞分裂丢失经由腺相关病毒导入的基因片段,因此腺相关病毒疗法不太适合以持续分裂的细胞(如干细胞)作为靶标[15]。

腺相关病毒作为基因治疗载体存在一些缺点。首先是容量低,最多只能容纳4.5kb的插入片段,无法容纳DMD等较长的人类基因[15]。其次,输入的腺相关病毒载体可能被体内存在的针对天然腺相关病毒的抗体中和。此外,腺相关病毒也存在整合入宿主基因组的情况[16]。

根据2019年的数据,全球范围内共有超过250件使用腺相关病毒载体技术的临床试验,占基于病毒载体的基因治疗临床试验的8.3%[17]。

参见

编辑参考文献

编辑- ^ Naso, Michael F.; Tomkowicz, Brian; Perry, William L.; Strohl, William R. Adeno-Associated Virus (AAV) as a Vector for Gene Therapy. BioDrugs. 2017, 31 (4): 317–334. ISSN 1173-8804. doi:10.1007/s40259-017-0234-5.

- ^ Wu, Zhijian; Yang, Hongyan; Colosi, Peter. Effect of Genome Size on AAV Vector Packaging. Molecular Therapy. 2010, 18 (1): 80–86. ISSN 1525-0016. doi:10.1038/mt.2009.255.

- ^ 3.0 3.1 Grieger JC, Samulski RJ. Adeno-associated Virus as a Gene Therapy Vector: Vector Development, Production and Clinical Applications. Adeno-associated virus as a gene therapy vector: vector development, production and clinical applications. Advances in Biochemical Engineering/Biotechnology 99. 2005: 119–45. ISBN 978-3-540-28404-8. PMID 16568890. doi:10.1007/10_005.

- ^ Deyle DR, Russell DW. Adeno-associated virus vector integration. Current Opinion in Molecular Therapeutics. August 2009, 11 (4): 442–7. PMC 2929125 . PMID 19649989.

- ^ Maguire AM, Simonelli F, Pierce EA, Pugh EN, Mingozzi F, Bennicelli J, et al. Safety and efficacy of gene transfer for Leber's congenital amaurosis. The New England Journal of Medicine. May 2008, 358 (21): 2240–8. PMC 2829748 . PMID 18441370. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0802315.

- ^ Carter BJ. Adeno-associated virus and the development of adeno-associated virus vectors: a historical perspective. Molecular Therapy. December 2004, 10 (6): 981–9. PMID 15564130. doi:10.1016/j.ymthe.2004.09.011 .

- ^ Adeno-Associated Virus and Adeno-associated Viral Vectors. [19 September 2018]. (原始内容存档于20 September 2018).

- ^ Daya, Shyam; Berns, Kenneth I. Gene Therapy Using Adeno-Associated Virus Vectors. Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 2008, 21 (4): 583–593. ISSN 0893-8512. doi:10.1128/CMR.00008-08.

- ^ Bohenzky RA, LeFebvre RB, Berns KI. Sequence and symmetry requirements within the internal palindromic sequences of the adeno-associated virus terminal repeat. Virology. October 1988, 166 (2): 316–27. PMID 2845646. doi:10.1016/0042-6822(88)90502-8.

- ^ Zhou X, Muzyczka N. In vitro packaging of adeno-associated virus DNA. Journal of Virology. April 1998, 72 (4): 3241–7. PMC 109794 . PMID 9525651. doi:10.1128/JVI.72.4.3241-3247.1998.

- ^ Wang XS, Ponnazhagan S, Srivastava A. Rescue and replication signals of the adeno-associated virus 2 genome. Journal of Molecular Biology. July 1995, 250 (5): 573–80. PMID 7623375. doi:10.1006/jmbi.1995.0398.

- ^ Weitzman MD, Kyöstiö SR, Kotin RM, Owens RA. Adeno-associated virus (AAV) Rep proteins mediate complex formation between AAV DNA and its integration site in human DNA. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. June 1994, 91 (13): 5808–12. Bibcode:1994PNAS...91.5808W. PMC 44086 . PMID 8016070. doi:10.1073/pnas.91.13.5808.

- ^ Jay FT, Laughlin CA, Carter BJ. Eukaryotic translational control: adeno-associated virus protein synthesis is affected by a mutation in the adenovirus DNA-binding protein. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. May 1981, 78 (5): 2927–31. Bibcode:1981PNAS...78.2927J. PMC 319472 . PMID 6265925. doi:10.1073/pnas.78.5.2927.

- ^ Sonntag F, Köther K, Schmidt K, Weghofer M, Raupp C, Nieto K, Kuck A, Gerlach B, Böttcher B, Müller OJ, Lux K, Hörer M, Kleinschmidt JA. The assembly-activating protein promotes capsid assembly of different adeno-associated virus serotypes. Journal of Virology. December 2011, 85 (23): 12686–97. PMC 3209379 . PMID 21917944. doi:10.1128/JVI.05359-11.

- ^ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Worgall, Stefan; Crystal, Ronald G. Gene therapy: 493–518. 2020. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-818422-6.00029-0.

- ^ Shams, Shahin; Silva, Eduardo A. Bioengineering strategies for gene delivery: 107–148. 2020. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-816221-7.00004-5.

- ^ Vectors used in Gene Therapy Clinical Trials. Journal of Gene Medicine. Wiley. December 2019 [4 January 2012]. (原始内容存档于21 October 2019).