User:Inzhrui/沙盒2

| 多孢植物 化石时期:晚奥陶界 - 现代

| |

|---|---|

| |

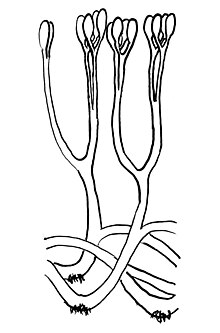

| Aglaophyton的复原图,图中显示了其有终端孢子囊和假根的分叉轴。 | |

| 科学分类 | |

| 界: | 植物界 Plantae |

| 演化支: | 链型植物 Streptophyta |

| 演化支: | 膜生植物 Phragmoplastophyta |

| 演化支: | 有胚植物 Embryophyta |

| 演化支: | 多孢植物 Polysporangiophyta Kenrick & Crane (1997) |

| 演化支 | |

| |

多胞植物(英語:Polysporangiophytes,也称polysporangiates或Polysporangiophyta),指的是在孢子体阶段有终止在孢子囊的分支的茎(轴)的植物。学名的意思即为有许多孢子囊的植物。演化支包含所有陆地植物(有胚植物),但孢子体不分支的苔藓植物(苔类、藓类和角苔纲)除外。此外有另外一种定义是指有独立的维管组织存在的植物,即维管植物,因为现存的所有多胞植物都有维管组织。但现已探明古多胞植物没有维管组织,不属于维管植物。

早期的多胞植物 编辑

发现的历史 编辑

古植物学家将微化石与大化石区分开来。微化石主要是单个或成组孢子。而大化石保存的植物体的部分已经足够大,可以展示植物体的结构,例如茎的截面或分支模式。[1]

道森,一位加拿大地质学家和古生物学家,最早发现和描述了多胞植物的大化石。1859年,他发表了一幅泥盆纪植物的复原图,收集自一枚来自加拿大加斯帕地区的化石, 并命名为Psilophyton princeps。重建图显示水平和直立的茎状结构;没有叶或根。竖直的茎或轴分支分布,附着着形成孢子的器官(孢子囊)。竖直轴上的横截面显示维管组织已经出现。他后来又描述了其他标本。道森的发现最初几乎没有科学影响;泰勒等人推测有可能是因为他重建的看起来很不寻常,并且化石年代实际比预期的的要古老。[2]

从1917年开始,Robert Kidston和William H. Lang发表了一系列的论文,描述了从莱尼燧石(一种在苏格兰阿伯丁郡的莱尼村附近发现的细颗粒沉积岩,现在确认它的年代是早泥盆世的布拉格期(约Template:Period span/brief))中发现的古植物。这些化石比道森的保存得更完好,清楚地显示了这些早期陆生植物确实包括一般垂直裸茎,且呈现类似水平结构。竖直的茎分布有顶端有孢子囊的分支。[2]

自此之后,在世界各地都在从志留纪到中泥盆世的地层中发现了类似的大化石,包括加拿大北极地区、美国东部、威尔士、德国莱茵兰、哈萨克斯坦、中国新疆和云南以及澳大利亚。[3]

分类 编辑

多胞植物的概念最早是由Kenrick和Crane在1997年提出的。[4](右边的分类代表他们对多胞植物的分类观点。)该演化支的定义特征是多个孢子体分叉,且承担多个孢子囊。由此可将多胞植物与地钱、苔藓和角苔等具有不分叉孢子体且每个孢子体只有一个孢子囊的植物区别。 多胞植物可能有也可能没有维管组织——具有维管组织的属于维管植物。

在此之前,大多数早期的多胞植物被放置在一个单独的目中,即在裸蕨纲中的裸蕨目,于1917年由Kidston和Lang创立。[5] 现存的松叶蕨有时被放入此纲,也通常被称为裸蕨类。[6]

随着发现和描述了更多的化石,确认了它与裸蕨植物是不同的植物类群。1975年,Banks详述了他早先在1968年将其分为三组的提议 ,并将其放在演化支的分类级别。[7][8]这些类群被分为门、[9]纲、[10]和目。[11]使用了许多种名称,如下表所示。

| 门 | 演化支 | 纲 | 目 | 非正式命名 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rhyniophyta | Rhyniophytina | Rhyniopsida (Rhyniophytopsida)[12] | Rhyniales | rhyniophyte |

| Zosterophyllophyta | Zosterophyllophytina | Zosterophyllopsida | Zosterophyllales | zosterophyll (zosterophyllophyte) |

| Trimerophyta (Trimerophytophyta)[13] | Trimerophytina (Trimerophytophytina) | Trimeropsida (Trimerophytopsida) | Trimerophytales | trimerophyte |

对Banks来说,莱尼蕨终端组成了简单的无叶植物的孢子囊(例如顶囊蕨、莱尼蕨)with centrarch xylem; zosterophylls comprised plants with lateral sporangia that split distally (away from their attachment) to release their spores, and had exarch strands of xylem (e.g., Gosslingia). Trimerophytes comprised plants with large clusters of downwards curving terminal sporangia that split along their length to release their spores and had centrarch xylem strands (e.g., Psilophyton).[14]

Research by Kenrick and Crane that established the polysporangiophytes concluded that none of Banks' three groups were monophyletic. The rhyniophytes included "protracheophytes", which were precursors to vascular plants (e.g., Horneophyton, Aglaophyton); basal tracheophytes (e.g., Stockmansella, Rhynia gwynne-vaughanii); and plants allied to the lineages that led to the living club-mosses and allies as well as ferns and seed plants (e.g., Cooksonia species). The zosterophylls did contain a monophyletic clade, but some genera previously included in the group fell outside this clade (e.g., Hicklingia, Nothia). The trimerophytes were paraphyletic stem groups to both the crown group ferns and the crown group seed plants.[15][16]

许多研究人员敦促谨慎地对早期多胞植物分类。Taylor et al. note that basal groups, such as early land plants, are inherently difficult to characterize since they share many characters with all later-evolving groups (i.e., have multiple plesiomorphies).[9] In discussing the classification of the trimerophytes, Berry and Fairon-Demaret say that reaching a meaningful classification requires "a breakthrough in knowledge and understanding rather than simply a reinterpretation of the existing data and the surrounding mythology".[17] Kenrick and Crane's cladograms have been questioned – see the Evolution section below.

截至2011年2月[update],尽管Cantino等人发表了Phylocode分类,根据Kenrick和Crane对进化枝的分析和后续研究似乎还是没有完成对早期多胞植物的林奈法分类。[18] Banks的三组分类由于其便利被沿用至今。[9]

种系发生 编辑

1997年,Kenrick和Crane发表了对主要的陆地植物演化支的研究,建立了多胞植物的概念和系统发生的概括。[4] Since 1997 there have been continual advances in understanding plant evolution, using RNA and DNA genome sequences and chemical analyses of fossils (例如Taylor等人2006[19]), resulting in revisions to this phylogeny.

In 2004, Crane et al. published a simplified cladogram for the polysporangiophytes (which they call polysporangiates), based on a number of figures in Kenrick and Crane (1997).[5] Their cladogram is reproduced below (with some branches collapsed into 'basal groups' to reduce the size of the diagram). Their analysis is not accepted by other researchers; for example Rothwell and Nixon say that the broadly defined fern group (moniliforms or monilophytes) is not monophyletic.[20]

| polysporangiophytes |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

More recently, Gerrienne and Gonez have suggested a slightly different characterization of the early diverging polysporangiophytes:[21]

| Polysporangiophytes |

| ||||||||||||

The paraphyletic protracheophytes, such as Aglaophyton, have water-conducting vessels like those of mosses, i.e., without cells containing thickened cell walls. The paratracheophytes, a name intended to replace Rhyniaceae or Rhyniopsida, have 'S-type' water-conducting cells, i.e., cells whose walls are thickened but in a much simpler fashion than those of true vascular plants, the eutracheophytes.[21]

进化 编辑

如果上面的发生树是正确的If the cladogram above is correct it has implications for the evolution of land plants. The earliest diverging polysporangiophytes in the cladogram are the Horneophytopsida, a clade at the 'protracheophyte' grade that is sister to all other polysporangiophytes. They had essentially an isomorphic alternation of generations (meaning that the sporophytes and gametophytes were equally free living), which might suggest that both the gametophyte-dominant life style of bryophytes and the sporophyte-dominant life style of vascular plants evolved from this isomorphic condition. They were leafless and did not have true vascular tissues. In particular, they did not have tracheids: elongated cells that help transport water and mineral salts, and that develop a thick lignified wall at maturity that provides mechanical strength. Unlike plants at the bryophyte grade, their sporophytes were branched.[22]

According to the cladogram, the genus Rhynia illustrates two steps in the evolution of modern vascular plants. Plants have vascular tissue, albeit significantly simpler than modern vascular plants. Their gametophytes are distinctly smaller than their sporophytes (but have vascular tissue, unlike almost all modern vascular plants).[23]

The remainder of the polysporangiophytes divide into two lineages, a deep phylogenetic split that occurred in the early to mid Devonian, around 400 million years ago. Both lineages have developed leaves, but of different kinds. The lycophytes, which make up less than 1% of the species of living vascular plants, have small leaves (microphylls or more specifically lycophylls), which develop from an intercalary meristem (i.e., the leaves effectively grow from the base). The euphyllophytes are by far the largest group of vascular plants, in terms of both individuals and species. Euphyllophytes have large 'true' leaves (megaphylls), which develop through marginal or apical meristems (i.e., the leaves effectively grow from the sides or the apex).[24]

Both the cladogram derived from Kenrick and Crane's studies and its implications for the evolution of land plants have been questioned by others. A 2008 review by Gensel notes that recently discovered fossil spores suggest that tracheophytes were present earlier than previously thought; perhaps earlier than supposed stem group members. Spore diversity suggests that there were many plant groups, of which no other remains are known. Some early plants may have had heteromorphic alternation of generations, with later acquisition of isomorphic gametophytes in certain lineages.[25]

上面的演化树显示“protracheophytes”的分化比lycophytes早;然而, lycophytes were present in the Ludfordian stage of the Silurian around Template:Period span/brief, long before the 'protracheophytes' found in the Rhynie chert, dated to the Pragian stage of the Devonian around Template:Period span/brief.[26] However, it has been suggested that the poorly preserved Eohostimella, found in deposits of Early Silurian age (Llandovery, around Template:Period span/brief), may be a rhyniophyte.[27]

博伊斯表示一些Cooksonia同属的孢子体的轴太窄,无法支持足够的光合作用,使它们独立于配子体发育,这与它们在演化树中的地位不符。[28]

植物的进化史还远未解决。

注释和引用 编辑

- ^ See, e.g., Edwards, D. & Wellman, C. (2001), "Embryophytes on Land: The Ordovician to Lochkovian (Lower Devonian) Record" in Gensel & Edwards 2001,第3–28頁

- ^ 2.0 2.1 Taylor, T.N.; Taylor, E.L. & Krings, M., Paleobotany, The Biology and Evolution of Fossil Plants 2nd, Amsterdam; Boston: Academic Press, 2009, ISBN 978-0-12-373972-8, p. 225ff

- ^ Gensel, P.G. & Edwards, D. (编), Plants invade the Land : Evolutionary & Environmental Perspectives, New York: Columbia University Press, 2001, ISBN 978-0-231-11161-4, chapters 2, 6, 7

- ^ 4.0 4.1 Kenrick & Crane 1997a,第139–140, 249頁

- ^ 5.0 5.1 Crane, P.R.; Herendeen, P. & Friis, E.M., Fossils and plant phylogeny, American Journal of Botany, 2004, 91 (10): 1683–99, PMID 21652317, doi:10.3732/ajb.91.10.1683

- ^ Taylor, Taylor & Krings 2009,第226頁.

- ^ Banks, H.P., The early history of land plants, Drake, E.T. (编), Evolution and Environment: A Symposium Presented on the Occasion of the 100th Anniversary of the Foundation of Peabody Museum of Natural History at Yale University, New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press: 73–107, 1968, cited in Banks 1980

- ^ Banks, H.P., Reclassification of Psilophyta, Taxon, 1975, 24 (4): 401–413, doi:10.2307/1219491

- ^ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Taylor, Taylor & Krings 2009,第227頁

- ^ See, e.g., Berry, C.M. & Fairon-Demaret, M. (2001), "The Middle Devonian Flora Revisited", in Gensel & Edwards 2001,第120–139頁

- ^ Banks, H.P., Evolution and Plants of the Past, London: Macmillan Press, 1970, ISBN 978-0-333-14634-7, p. 57

- ^ Although this name has appeared in some sources, e.g., Knoll, Andrew H., Review of The Origin and Early Diversification of Land Plants: A Cladistic Study by Paul Kenrick; Peter Crane, International Journal of Plant Sciences, 1998-01-01, 159 (1): 172–174, JSTOR 2474949, doi:10.1086/297535, it appears to be a mistake, as it is not in accord with Article 16 of the International Code of Botanical Nomenclature.

- ^ The name is based on the genus Trimerophyton; Article 16.4 of the International Code of Botanical Nomenclature allows the phyton part to be omitted before -ophyta, -ophytina, and -opsida.

- ^ Banks, H.P., The role of Psilophyton in the evolution of vascular plants, Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology, 1980, 29: 165–176, doi:10.1016/0034-6667(80)90056-1

- ^ Kenrick, Paul & Crane, Peter R., The Origin and Early Diversification of Land Plants: A Cladistic Study, Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1997a, ISBN 978-1-56098-730-7

- ^ Kenrick, P. & Crane, P.R., The origin and early evolution of plants on land, Nature, 1997b, 389 (6646): 33–39, Bibcode:1997Natur.389...33K, doi:10.1038/37918

- ^ Berry & Fairon-Demaret 2001,第127頁

- ^ Cantino, Philip D.; James A. Doyle; Sean W. Graham; Walter S. Judd; Richard G. Olmstead; Douglas E. Soltis; Pamela S. Soltis; Michael J. Donoghue, Towards a Phylogenetic Nomenclature of Tracheophyta, Taxon, 2007, 56 (3): 822–846, doi:10.2307/25065865

- ^ Taylor, D.W.; Li, Hongqi; Dahl, Jeremy; Fago, F.J.; Zinneker, D.; Moldowan, J.M., Biogeochemical evidence for the presence of the angiosperm molecular fossil oleanane in Paleozoic and Mesozoic non-angiospermous fossils, Paleobiology, 2006, 32 (2): 179–90, ISSN 0094-8373, doi:10.1666/0094-8373(2006)32[179:BEFTPO]2.0.CO;2

- ^ Rothwell, G.W. & Nixon, K.C., How Does the Inclusion of Fossil Data Change Our Conclusions about the Phylogenetic History of Euphyllophytes?, International Journal of Plant Sciences, 2006, 167 (3): 737–749, doi:10.1086/503298

- ^ 21.0 21.1 Gerrienne, P. & Gonez, P., Early evolution of life cycles in embryophytes: A focus on the fossil evidence of gametophyte/sporophyte size and morphological complexity, Journal of Systematics and Evolution, 2011, 49: 1–16, doi:10.1111/j.1759-6831.2010.00096.x

- ^ Bateman, R.M.; Crane, P.R.; Dimichele, W.A.; Kenrick, P.R.; Rowe, N.P.; Speck, T.; Stein, W.E., Early Evolution of Land Plants: Phylogeny, Physiology, and Ecology of the Primary Terrestrial Radiation, Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics, 1998, 29 (1): 263–92, doi:10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.29.1.263, p. 270

- ^ Kerp, H.; Trewin, N.H. & Hass, H., New gametophytes from the Early Devonian Rhynie chert, Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh: Earth Sciences, 2004, 94: 411–28, doi:10.1017/s026359330000078x

- ^ Pryer, K.M.; Schuettpelz, E.; Wolf, P.G.; Schneider, H.; Smith, A.R.; Cranfill, R., Phylogeny and evolution of ferns (monilophytes) with a focus on the early leptosporangiate divergences, American Journal of Botany, 2004, 91 (10): 1582–98 [2011-01-29], PMID 21652310, doi:10.3732/ajb.91.10.1582, pp. 1582–3

- ^ Gensel, Patricia G., The Earliest Land Plants, Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst., 2008, 39: 459–77, doi:10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.39.110707.173526, pp. 470–2

- ^ Kotyk, M.E.; Basinger, J.F.; Gensel, P.G. & de Freitas, T.A., Morphologically complex plant macrofossils from the Late Silurian of Arctic Canada, Am. J. Bot., 2002, 89 (6): 1004–1013, PMID 21665700, doi:10.3732/ajb.89.6.1004

- ^ Niklas, K.J., An Assessment of Chemical Features for the Classification of Plant Fossils, Taxon, 1979, 28 (5/6): 505, doi:10.2307/1219787

- ^ Boyce, C.K., How green was Cooksonia? The importance of size in understanding the early evolution of physiology in the vascular plant lineage, Paleobiology, 2008, 34 (2): 179–194, ISSN 0094-8373, doi:10.1666/0094-8373(2008)034[0179:HGWCTI]2.0.CO;2

外部链接 编辑

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|