海洋热含量

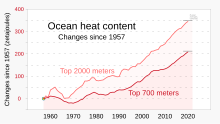

海洋热含量(英语:Ocean heat content,缩写:OHC)是指海洋吸收和储存的热能。为了计算海洋热含量,需要测量各地海洋不同位置和深度的温度,并积分整个海洋的热量面密度[注 1],即可得出海洋总热量。[2]1971年至2018年间,海洋热含量的增加占全球暖化导致的地球过剩热能的九成以上。[3][4]海洋热含量增加的主要因素是温室气体排放增加。[5]:1228截至2020年,大约三分之一的过剩热量已传播到700米以下的深海。[6][7]2022年世界海洋热含量超过了2021年的记录,再度成为历史记录中最热的水平。[8]在2019至2022年间,北太平洋、北大西洋、地中海和南冰洋这四个地区打破了六十多年来的最高热量观测结果。[9]海洋热含量和海平面上升是气候变化的重要指标。[10]

海水容易吸收太阳能,并且热容量远大于大气气体。[6] 因此,海洋顶部几米所包含的热能比整个地球大气层还多。[11]早在1960年以前,研究船和研究站便已开始在世界各地对海面温度和更深处的温度进行了采样。此外,自2000年以来,由近4000个机器人组成的Argo计划拓展了测量能力,更能呈现了温度异常的情况和海洋热含量的变化。已知至少自1990年以来,海洋热含量就不断稳定增长,甚至加速增长。[3][12]2003-2018年间,在深度小于2000米的区域内,平均每年增加9.3泽焦耳(这相当于 0.58±0.08 W/m2 的能量增长速率)。测量的不确定性主要是来自测量精度、空间覆盖范围,及持续数十年不间断测量的三方面挑战。[10]

海洋热含量的变化对地球的海洋和陆地生态系统皆产生深远的影响;当中包含对沿海生态系统的多重影响。直接影响包括海平面和海冰的变化、水循环强度的变化以及海洋生物的迁徙和灭绝。[13][14]

计算 编辑

定义 编辑

海洋热含量是“海洋储存的热量总量”,[15]因此需要先测量许多不同位置和深度的海洋温度才能计出海洋热含量。

对整个海洋的海洋热量密度进行积分,即可得出海洋总热量。[16]

算是中 是海水的比热容,h2是深边界,h1是浅边界, 海水密度, 是温度。在国际单位制中, 的单位为焦耳每平方米(J·m−2)。

务实上,可以透过一些近似函数简化测量与计算。海水密度是温度、盐度和压力的函数值。尽管在海洋深处寒冷且压力巨大,但由于水几乎不可压缩,且为稳定的液体状态,深海水密度已达到最大值。

温度与海洋深度的测量将描绘出上层混合层(0-200米)、温跃层(200-1500米)和深海层(>1500米)。这些界限深度只是粗略的近似值。阳光最大穿透深度约为200米;其中最上面的80米是光合作用海洋生物的生活区,覆盖地球表面超过70%的区域。[18]波浪作用和其他表面湍流有助于让上层性质更为均匀一致。

表面温度会随着纬度增加而递减;而世界上大多数地区的深海温度相对较低且均匀。[19]大约50%的海洋体积位于超过3000米的深度,其中太平洋是五个海洋区分中最大且最深的。温跃层是上层和深层之间的过渡区,涉及温度、养分流动、生物丰富度等多个层面。在热带地区,它是半永久性的;在温带地区,它是会随着季节变动;而在极地地区,它很浅,甚至不存在。[20]

测量 编辑

海洋热含量的测量相当困难,尤其是在Argo剖面浮标部署之前。由于空间覆盖不足和数据质量不佳,有时很难区分长期全球暖化趋势和气候变异的影响。这些复杂因素的示例包括由于厄尔尼诺现象和重大火山爆发引起的海洋热含量变化。[10]

Argo是一个自21世纪初开始部署的机器人剖面浮标国际计划。[22] 该计划最初的3000个单元在2020年扩展到近4000个单元。在每个10天的测量周期开始时,浮标会下降到1000米的深度,漂流九天。然后,它会下降到2000米的深度,并在最后一天上升到表面时测量温度、盐度(电导率)和深度(压力)。在表面,浮标通过卫星中继传输深度剖面和水平位置数据,然后重复周期。[23]

从1992年开始,TOPEX/Poseidon和随后的Jason卫星系列观测到了垂直积分的海洋热含量,这是海平面上升的主要组成部分之一。[24] Argo和Jason测量之间的合作让海洋热含量和其他全球海洋特性的测量更为精准。[21]

热含量上升的原因 编辑

地球的热带表面水体吸收大量的太阳辐射热,并推动了海洋热的传播链,一路到达极地。海洋表面还会与下层对流层进行能量交换,因此对地球能量收支中的云层反照率、温室气体和其他因素也有交互作用。[6] 随着时间的推移,不平衡的能量收支使得热量通过热传导、下沉流和上升流,流入海洋各处。[26][27]

海洋是地球最大的热库,同时兼具能量的储存与释放的作用,可以调节行星的气候。[28] 海洋热含量主要透过蒸发向大气的释放,这也促使了行星的水循环。[29] 海洋表面温度较高时,集中的释放可生成热带气旋、大气河流、大气热浪以及其他极端天气事件,这些事件可以深入内陆地区。[16][30]

海洋还作为碳的储存和释放地,其在地球碳循环中的作用与陆地地区相当。[31][32] 根据亨利定律的温度依赖性,升温的表面水体较难吸收大气中的气体,包括来自人类活动的二氧化碳和其他温室气体。[33][34]

近期观察与变化 编辑

近年来的众多独立研究发现上层海洋区域的海洋热含量十年的上升趋势,并且已经开始向更深的地区扩散。[36]

研究表明,自1971年以来,上层海洋(0-700米)已经升温,同时中等深度(700-2000米)可能也发生了升温,而深海(2000米以下)的温度可能也有所增加。[5]:1228 这种热量吸收是由于地球能量收支中持续存在的升温不平衡所导致的,刨根究底,是由人类活动排放的温室气体造成。[37]:41 从1960年代初到2010年代末,海洋吸收的人为排放二氧化碳的速率大约增加了两倍,这与大气二氧化碳的增加成正比。[38] 非常肯定,人为二氧化碳排放导致的海洋热含量增加在人类时间尺度上基本上是不可逆转的。[5]:1233

基于Argo测量的研究表明,海洋表面风,尤其是太平洋的信风,会改变海洋的热垂直分布。[39] 这导致洋流的变化,这也与厄尔尼诺现象和反圣婴现象有关。根据随机自然变异的波动,反圣婴年份将有大约30%的热从上层海洋层运输到更深的海洋中。此外,研究表明,观察到的海洋升温约有三分之一发生在700至2000米的海洋层。[40]

模型研究显示,在反圣婴年份,洋流在风循环变化后将更多的热量输送到更深的层次中。[41][42] 海洋热量吸收增加的年份通常与太平洋十年涛动的负相位有关。[43] 这对于气候科学家来说十分有趣,他们使用这些数据来估算海洋的热量吸收情况。

北大西洋大部分地区的上层海洋热量以热传输汇聚(洋流交汇的位置)为主。[44] 此外,2022 年关于人为海洋暖化的一项研究表明,1850年至2018年间北大西洋沿 25°N 的变暖有62% 存在于700m以下的水中。大部分海洋多余的热量都被储存在那里。[45]

自1970年代以来,海洋2000米内平均升温,但海洋升温的速率因地而异,亚极北大西洋升温速度较慢;而南冰洋由于人为排放的温室气体,吸收了不成比例的大量热量。[5]:1230

影响 编辑

海洋暖化造成了珊瑚白化,[46] 也导致了海洋生物的迁徙,[47]并使海洋热浪更加频繁。[48] 大气环流和海洋洋流将行星内部能量重新分布,产生内部气候变异,通常以不规则振荡的形式呈现,[49] 并有助于维持温盐环流。[50] [51]

自1900年至2020年,海洋热含量的增加导致的热膨胀占全球海平面上升的30-40%。[52][53] 海洋热含量还加速了海冰、冰山和潮水冰河的融化。冰的损失降低了极地的反照率,放大了区域和全球的能量不平衡。[54] 北极海冰的融退也因此迅速而广泛。[55]同样在北极地区的峡湾,如格陵兰和加拿大的峡湾中也出现了冰融退。[56]对于南极海冰和广阔的南极冰棚,其影响因地区而异。由于海水的升温,影响正逐渐增加。[57][58] 2020年,特威茨冰棚及其西南极邻居的瓦解对于海平面上升贡献了约10%。[59][60]

2015年的一项研究得出结论,太平洋海域的海洋热含量增加被突然转移到了印度洋。[61]

参见 编辑

注释 编辑

参考文献 编辑

- ^ Top 700 meters: Lindsey, Rebecca; Dahlman, Luann. Climate Change: Ocean Heat Content. climate.gov. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). 6 September 2023. (原始内容存档于29 October 2023). ● Top 2000 meters: Ocean Warming / Latest Measurement: December 2022 / 345 (± 2) zettajoules since 1955. NASA.gov. National Aeronautics and Space Administration. (原始内容存档于20 October 2023).

- ^ 2.0 2.1 Kumar, M. Suresh; Kumar, A. Senthil; Ali, MM. Computation of Ocean Heat Content (PDF). Technical Report NRSC-SDAPSA-G&SPG-DEC-2014-TR-672 (National Remote Sensing Centre (ISRO), Government of India). 10 December 2014 [2023-08-23]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2023-04-12).

- ^ 3.0 3.1 3.2 von Schuckman, K.; Cheng, L.; Palmer, M. D.; Hansen, J.; et al. Heat stored in the Earth system: where does the energy go?. Earth System Science Data. 2020-09-07, 12 (3): 2013-2041. Bibcode:2020ESSD...12.2013V. doi:10.5194/essd-12-2013-2020 .

- ^ Cheng, Lijing; Abraham, John; Trenberth, Kevin; Fasullo, John; Boyer, Tim; Locarnini, Ricardo; et al. Upper Ocean Temperatures Hit Record High in 2020. Advances in Atmospheric Sciences. 2021, 38 (4): 523–530. Bibcode:2021AdAtS..38..523C. S2CID 231672261. doi:10.1007/s00376-021-0447-x .

- ^ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 Fox-Kemper, B., H.T. Hewitt, C. Xiao, G. Aðalgeirsdóttir, S.S. Drijfhout, T.L. Edwards, N.R. Golledge, M. Hemer, R.E. Kopp, G. Krinner, A. Mix, D. Notz, S. Nowicki, I.S. Nurhati, L. Ruiz, J.-B. Sallée, A.B.A. Slangen, and Y. Yu, 2021: Chapter 9: Ocean, Cryosphere and Sea Level Change 互联网档案馆的存档,存档日期2022-10-24.. In Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change 互联网档案馆的存档,存档日期2021-08-09. [Masson-Delmotte, V., P. Zhai, A. Pirani, S.L. Connors, C. Péan, S. Berger, N. Caud, Y. Chen, L. Goldfarb, M.I. Gomis, M. Huang, K. Leitzell, E. Lonnoy, J.B.R. Matthews, T.K. Maycock, T. Waterfield, O. Yelekçi, R. Yu, and B. Zhou (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, pp. 1211–1362.

- ^ 6.0 6.1 6.2 LuAnn Dahlman and Rebecca Lindsey. Climate Change: Ocean Heat Content. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. 2020-08-17 [2023-08-23]. (原始内容存档于2023-02-25).

- ^ Study: Deep Ocean Waters Trapping Vast Store of Heat. Climate Central. 2016 [2023-08-23]. (原始内容存档于2020-01-29).

- ^ Cheng, Lijing; Abraham, John; Trenberth, Kevin E.; Fasullo, John; Boyer, Tim; Mann, Michael E.; Zhu, Jiang; Wang, Fan; Locarnini, Ricardo; Li, Yuanlong; Zhang, Bin; Yu, Fujiang; Wan, Liying; Chen, Xingrong; Feng, Licheng. Another Year of Record Heat for the Oceans. Advances in Atmospheric Sciences. 2023, 40 (6): 963–974. Bibcode:2023AdAtS..40..963C. ISSN 0256-1530. PMC 9832248 . PMID 36643611. doi:10.1007/s00376-023-2385-2 (英语).

- ^ NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information, Monthly Global Climate Report for Annual 2022, published online January 2023, Retrieved on July 25, 2023 from https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/access/monitoring/monthly-report/global/202213 (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆).

- ^ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Cheng, Lijing; Foster, Grant; Hausfather, Zeke; Trenberth, Kevin E.; Abraham, John. Improved Quantification of the Rate of Ocean Warming. Journal of Climate. 2022, 35 (14): 4827–4840 [2023-08-23]. Bibcode:2022JCli...35.4827C. doi:10.1175/JCLI-D-21-0895.1 . (原始内容存档于2017-10-16).

- ^ Vital Signs of the Plant: Ocean Heat Content. NASA. [2021-11-15]. (原始内容存档于2022-11-22).

- ^ Abraham, J. P.; Baringer, M.; Bindoff, N. L.; Boyer, T.; et al. A review of global ocean temperature observations: Implications for ocean heat content estimates and climate change. Reviews of Geophysics. 2013, 51 (3): 450–483. Bibcode:2013RvGeo..51..450A. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.594.3698 . S2CID 53350907. doi:10.1002/rog.20022. hdl:11336/25416.

- ^ Dean Roemmich. How long until ocean temperature goes up a few more degrees?. 斯克里普斯海洋研究所. 2014-03-18 [2023-08-17]. (原始内容存档于2023-06-01).

- ^ Ocean warming : causes, scale, effects and consequences. And why it should matter to everyone. Executive summary (PDF). 国际自然保护联盟. 2016 [2023-08-17]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2023-01-23).

- ^ US EPA, OAR. Climate Change Indicators: Ocean Heat. www.epa.gov. 2016-06-27 [2023-02-28]. (原始内容存档于2023-08-21) (英语).

- ^ 16.0 16.1 OHC reaches its highest level in recorded history. National Centers for Environmental Information. 22 January 2020 [2023-08-23]. (原始内容存档于2023-08-01).

- ^ Dijkstra, Henk A. Dynamical oceanography [Corr. 2nd print.] Berlin: Springer Verlag. 2008: 276. ISBN 9783540763758.

- ^ photic zone (oceanography). Encyclopædia Britannica Online. [2021-12-15]. (原始内容存档于2015-05-08).

- ^ MarineBio. The Deep Sea. MarineBio Conservation Society. 2018-06-17 [2020-08-07]. (原始内容存档于2023-08-23) (美国英语).

- ^ What is a thermocline?. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. [2021-12-23]. (原始内容存档于2023-05-25) (英语).

- ^ 21.0 21.1 About Argo. Scripps Institute of Oceanography, UC San Diego. [27 January 2023]. (原始内容存档于2023-08-05).

- ^ Toni Feder. Argo Begins Systematic Global Probing of the Upper Oceans. Physics Today. 2000, 53 (7): 50. Bibcode:2000PhT....53g..50F. doi:10.1063/1.1292477.

- ^ Dale C.S. Destin. The Argo revolution. climate.gov. 5 December 2014 [2023-08-23]. (原始内容存档于2023-08-23).

- ^ Ocean Surface Topography from Space: Ocean warming estimates from Jason. NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory. 29 January 2020 [2023-08-23]. (原始内容存档于2023-01-27).

- ^ Global Ocean Heat and Salt Content: Seasonal, Yearly, and Pentadal Fields. NOAA. [2022-02-26]. (原始内容存档于2023-07-27).

- ^ Air-Sea interaction: Teacher's guide. 美国气象学会. 2012 [2022-02-22]. (原始内容存档于2023-04-12).

- ^ Ocean Motion : Definition : Wind Driven Surface Currents - Upwelling and Downwelling. [2022-02-22]. (原始内容存档于2022-01-11).

- ^ Michon Scott. Earth's Big Heat Bucket. NASA Earth Observatory. 2006-04-24 [2023-08-23]. (原始内容存档于2023-02-09).

- ^ NASA Earth Science: Water Cycle. NASA. [2021-10-27]. (原始内容存档于2023-06-09).

- ^ Laura Snider. 2020 was a record-breaking year for ocean heat - Warmer ocean waters contribute to sea level rise and strengthen storms. 美国国家大气研究中心. 2021-01-13 [2023-08-23]. (原始内容存档于2023-08-23).

- ^ Friedlingstein, M., O'Sullivan, M., M., Jones, Andrew, R., Hauck, J., Olson, A., Peters, G., Peters, W., Pongratz, J., Sitch, S., Le Quéré, C. and 75 others. Global carbon budget 2020. Earth System Science Data. 2020, 12 (4): 3269–3340. Bibcode:2020ESSD...12.3269F. doi:10.5194/essd-12-3269-2020 .

- ^ Riebeek, Holli. The Carbon Cycle. Earth Observatory. NASA. 16 June 2011 [2022-2-26]. (原始内容存档于5 March 2016).

- ^ Woolf D. K., Land P. E., Shutler J. D., Goddijn-Murphy L.M., Donlon, C. J. On the calculation of air-sea fluxes of CO2 in the presence of temperature and salinity gradients. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans. 2016, 121 (2): 1229–1248. Bibcode:2016JGRC..121.1229W. doi:10.1002/2015JC011427 .

- ^ Riebeek, Holli. The Ocean's Carbon Cycle. Earth Observatory. NASA. 1 July 2008 [2022-2-26]. (原始内容存档于2022-11-16).

- ^ Jessica Blunden. Reporting on the State of the Climate in 2020. Climate.gov. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. 25 August 2021 [2023-08-23]. (原始内容存档于2022-12-31).

- ^ Abraham; et al. A review of global ocean temperature observations: Implications for ocean heat content estimates and climate change. Reviews of Geophysics. 2013, 51 (3): 450–483. Bibcode:2013RvGeo..51..450A. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.594.3698 . S2CID 53350907. doi:10.1002/rog.20022.

- ^ Arias, P.A., N. Bellouin, E. Coppola, R.G. Jones, G. Krinner, J. Marotzke, V. Naik, M.D. Palmer, G.-K. Plattner, J. Rogelj, M. Rojas, J. Sillmann, T. Storelvmo, P.W. Thorne, B. Trewin, K. Achuta Rao, B. Adhikary, R.P. Allan, K. Armour, G. Bala, R. Barimalala, S. Berger, J.G. Canadell, C. Cassou, A. Cherchi, W. Collins, W.D. Collins, S.L. Connors, S. Corti, F. Cruz, F.J. Dentener, C. Dereczynski, A. Di Luca, A. Diongue Niang, F.J. Doblas-Reyes, A. Dosio, H. Douville, F. Engelbrecht, V. Eyring, E. Fischer, P. Forster, B. Fox-Kemper, J.S. Fuglestvedt, J.C. Fyfe, N.P. Gillett, L. Goldfarb, I. Gorodetskaya, J.M. Gutierrez, R. Hamdi, E. Hawkins, H.T. Hewitt, P. Hope, A.S. Islam, C. Jones, et al. 2021: Technical Summary 互联网档案馆的存档,存档日期2022-07-21.. In Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change 互联网档案馆的存档,存档日期2021-08-09. [Masson-Delmotte, V., P. Zhai, A. Pirani, S.L. Connors, C. Péan, S. Berger, N. Caud, Y. Chen, L. Goldfarb, M.I. Gomis, M. Huang, K. Leitzell, E. Lonnoy, J.B.R. Matthews, T.K. Maycock, T. Waterfield, O. Yelekçi, R. Yu, and B. Zhou (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, pp. 33−144.

- ^ Gruber, Nicolas; Bakker, Dorothee; DeVries, Tim; Gregor, Luke; Hauck, Judith; Landschützer, Peter; McKinley, Galen; Müller, Jens. Trends and variability in the ocean carbon sink. Nature Reviews Earth & Environment. 24 January 2023, 4 (2): 119–134 [2023-08-23]. Bibcode:2023NRvEE...4..119G. S2CID 256264357. doi:10.1038/s43017-022-00381-x. (原始内容存档于2023-05-01).

- ^ Balmaseda, Trenberth & Källén. Distinctive climate signals in reanalysis of global ocean heat content. Geophysical Research Letters. 2013, 40 (9): 1754–1759. Bibcode:2013GeoRL..40.1754B. doi:10.1002/grl.50382 . Essay 互联网档案馆的存档,存档日期2015-02-13.

- ^ Levitus, Sydney. World ocean heat content and thermosteric sea level change (0–2000 m), 1955–2010. Geophysical Research Letters. 17 May 2012, 39 (10): 1–3 [28 April 2023]. Bibcode:2012GeoRL..3910603L. ISSN 0094-8276. S2CID 55809622. doi:10.1029/2012GL051106 . (原始内容存档于2023-08-23).

- ^ Meehl; et al. Model-based evidence of deep-ocean heat uptake during surface-temperature hiatus periods. Nature Climate Change. 2011, 1 (7): 360–364. Bibcode:2011NatCC...1..360M. doi:10.1038/nclimate1229.

- ^ Rob Painting. The Deep Ocean Warms When Global Surface Temperatures Stall. SkepticalScience.com. 2 October 2011 [15 July 2016]. (原始内容存档于2019-06-12).

- ^ Rob Painting. A Looming Climate Shift: Will Ocean Heat Come Back to Haunt us?. SkepticalScience.com. 24 June 2013 [15 July 2016]. (原始内容存档于2019-10-09).

- ^ Sirpa Häkkinen; Peter B Rhines; Denise L Worthen. Heat content variability in the North Atlantic Ocean in ocean reanalyses. Geophys Res Lett. 2015, 42 (8): 2901–2909. Bibcode:2015GeoRL..42.2901H. PMC 4681455 . PMID 26709321. doi:10.1002/2015GL063299.

- ^ Messias, Marie-José; Mercier, Herlé. The redistribution of anthropogenic excess heat is a key driver of warming in the North Atlantic. Communications Earth & Environment. 17 May 2022, 3 (1): 118 [27 April 2023]. Bibcode:2022ComEE...3..118M. ISSN 2662-4435. S2CID 248816280. doi:10.1038/s43247-022-00443-4 . (原始内容存档于2023-05-01) (英语).

- ^ The Great Barrier Reef: a catastrophe laid bare. The Guardian. 6 June 2016 [2023-08-23]. (原始内容存档于2020-01-06).

- ^ Poloczanska, Elivra S.; Brown, Christopher J.; Sydeman, William J.; Kiessling, Wolfgang; Schoeman, David S.; Moore, Pippa J.; et al. Global imprint of climate change on marine life. Nature Climate Change. 2013, 3 (10): 919–925 [2023-08-17]. Bibcode:2013NatCC...3..919P. doi:10.1038/nclimate1958. (原始内容存档于2023-05-28).

- ^ So what are marine heat waves? - A NOAA scientist explains. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. 2019-10-08 [2023-08-23]. (原始内容存档于2022-01-24).

- ^ El Niño & Other Oscillations. Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. [2021-10-08]. (原始内容存档于2019-04-06).

- ^ Rahmstorf, Stefan. The concept of the thermohaline circulation. Nature. 2003, 421 (6924): 699. Bibcode:2003Natur.421..699R. PMID 12610602. S2CID 4414604. doi:10.1038/421699a .

- ^ Rahmstorf, Stefan; Box, Jason E.; Feulner, George; Mann, Michael E.; Robinson, Alexander; Rutherford, Scott; Schaffernicht, Erik J. Exceptional twentieth-century slowdown in Atlantic Ocean overturning circulation (PDF). 自然气候变化. 2015, 5 (5): 475–480 [2023-08-23]. Bibcode:2015NatCC...5..475R. doi:10.1038/nclimate2554. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2022-10-23).

- ^ Frederikse, Thomas; Landerer, Felix; Caron, Lambert; Adhikari, Surendra; Parkes, David; Humphrey, Vincent W.; et al. The causes of sea-level rise since 1900. Nature. 2020, 584 (7821): 393–397. PMID 32814886. S2CID 221182575. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2591-3.

- ^ NASA-led study reveals the causes of sea level rise since 1900. NASA. 2020-08-21 [2023-08-23]. (原始内容存档于2023-08-23).

- ^ Garcia-Soto, Carlos. An Overview of Ocean Climate Change Indicators: Sea Surface Temperature, Ocean Heat Content, Ocean pH, Dissolved Oxygen Concentration, Arctic Sea Ice Extent, Thickness and Volume, Sea Level and Strength of the AMOC (Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation). Frontiers in Marine Science. 2022-10-20, 8. doi:10.3389/fmars.2021.642372 .

- ^ Rebecca Lindsey and Michon Scott. Climate Change: Arctic sea ice. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. 2021-09-21 [2023-08-23]. (原始内容存档于2021-10-11).

- ^ Maria-Jose Viñas and Carol Rasmussen. Warming seas and melting ice sheets. NASA. 2015-08-05 [2023-08-23]. (原始内容存档于2023-06-07).

- ^ Slater, Thomas; Lawrence, Isobel R.; Otosaka, Inès N.; Shepherd, Andrew; et al. Review article: Earth's ice imbalance. The Cryosphere. 25 January 2021, 15 (1): 233–246. Bibcode:2021TCry...15..233S. doi:10.5194/tc-15-233-2021 .

- ^ Michon Scott. Understanding climate: Antarctic sea ice extent. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. 2021-03-26 [2023-08-23]. (原始内容存档于2021-03-24).

- ^ Carly Cassella. Warm Water Under The 'Doomsday Glacier' Threatens to Melt It Faster Than We Predicted. sciencealert.com. 2021-04-11 [2023-08-23]. (原始内容存档于2023-03-23).

- ^ British Antarctic Survey. The threat from Thwaites: The retreat of Antarctica's riskiest glacier. phys.org. 2021-12-15 [2023-08-23]. (原始内容存档于2023-05-30).

- ^ Lee, Sang-Ki; Park, Wonsun; Baringer, Molly O.; Gordon, Arnold L.; Huber, Bruce; Liu, Yanyun. Pacific origin of the abrupt increase in Indian Ocean heat content during the warming hiatus. Nature Geoscience. June 2015, 8 (6): 445–449. Bibcode:2015NatGe...8..445L. doi:10.1038/ngeo2438. hdl:1834/9681 .

- ^ Adam Voiland and Joshua Stevens. Methane Matters. NASA Earth Observatory. 8 March 2016 [2022-2-26]. (原始内容存档于2023-06-08).