用户:Koala0090/失智症

此用户页目前正依照其他维基百科上的内容进行翻译。 (2021年10月9日) |

| 失智症 | |

|---|---|

| 又称 | 老人痴呆症[1]、重度神经认知障碍症(Major neurocognitive disorder) |

| |

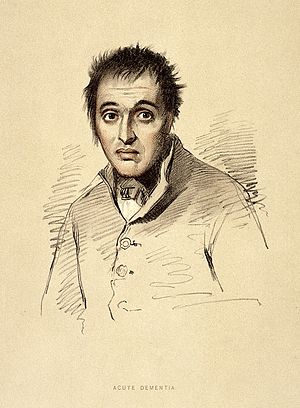

| 1880年描绘失智症患者的版画 | |

| 症状 | 思考及记忆功能减退、情绪障碍、语言功能受损、动机减退[2][3] |

| 起病年龄 | 渐发性[2] |

| 病程 | 长期[2] |

| 病因 | 阿兹海默症、血管性痴呆、路易氏体失智症、额颞叶型失智症[4][3] |

| 诊断方法 | 认知功能测验(简短智能测验)[3][5] |

| 鉴别诊断 | 谵妄[6]、甲状腺机能低下症 |

| 预防 | 及早接受教育、避免高血压、避免肥胖、戒烟或禁烟、社会参与[7] |

| 治疗 | 支持性疗法[2] |

| 药物 | 乙酰胆碱酯酶抑制剂(效果有限)[8][9] |

| 患病率 | 5000万(2020年)[4] |

| 死亡数 | 240万(2016年)[10] |

| 分类和外部资源 | |

| 医学专科 | 神经内科、身心医学 |

| “Dementia”的各地常用译名 | |

|---|---|

| 中国大陆 | 痴呆症 |

| 台湾 | 失智症 |

| 香港 | 认知障碍症 |

| 澳门 | 脑退化症 |

失智症(英语:dementia),是囊括许多脑部神经性疾病的泛称[11]。长期下来,患者的思考能力和记忆力会逐渐减弱、退化,并对其日常生活功能造成影响[4]。其他常见症状有情绪问题、语言困难以及意志缺失[2][3]。失智症并不属于意识障碍,患者的意识通常不受影响[4][a]。若要诊断一个人得了失智症,患者必须要有心智功能减退,且其减退程度较正常老化严重[4][13]。DSM-5将失智症归类为一种重性神经认知失调病(major neurocognitive disorder)。失智症可能是因某些疾病或脑部损伤所致,其下包含许多病因所造成的不同亚型[14]。失智症也常会对患者及其照顾者之间的关系造成一定程度的冲击[4]。

最常见的失智症类型为阿兹海默症,约占总患者数的五到七成[2][3]。其他常见的种类有血管性痴呆25%、路易氏体失智症15%,以及额颞叶型失智症[3][2]。较少见的成因则有常压型水脑症、帕金森氏症型失智症、梅毒、人类免疫缺乏病毒型失智症以及克雅二氏病等[15]。一位患者可能同时罹患两种(含)以上的失智症[2]。家族遗传的患者所占比例不多[16]。在精神疾病诊断与统计手册第五版中,将失智症视为一种认知障碍,并依其严重程度进行分类[14]。诊断失智症时,通常需根据患者的病史,辅以一系列的认知测验与医学影像和血液检查结果,来排除其他可能的病因[5]。例如简短智能测验,就是一种常见的认知测验工具[3]。预防失智症的方法为减少常见危险因子,如高血压、吸烟、糖尿病以及肥胖症等[2]。目前并不建议全面对一般民众进行失智症筛检[17]。

目前尚无方法可治愈失智症[2]。临床常用乙酰胆碱酯酶抑制剂(AChEI)型药物,例如多奈哌齐;此类药物或许对轻至中度失智症有效[8][18][19],但药效终归有限[8][9]。对患者与其照护者而言,仍有不少方法能有助改善其生活品质,像是认知行为疗法[2]。另外,对照护者提供卫教与情感支持也很重要[2]。运动有助于病患的日常生活活动,且有望改善预后[20]。此症带来的行为问题,常以抗精神病药治疗,但一般而言不特别推荐,因疗效有限且有副作用,可能会提高患者的死亡风险[21][22]。

2015年,全球失智症患者约有4,600万人[23]。终身盛行率约为10%,意即全球约有一成人口,终其一生有机会罹患此症[16]。失智症与老化显然有其关联[24],65到74岁的族群中,约有3%罹患失智症;75到84岁族群中则有 19%,而85岁以上者,几乎一半以上是患者[25]。1990年,此症造成80万人死亡,但是2013年,死亡人数升高至1,700万[26]。随著人类寿命延长,此症也更形普遍[24]。然而特定年龄层的盛行率却可能反而是比较低的,至少已开发国家有这样的倾向,是由于风险因子减少之故[24]。此症是老年族群中,最常见的身心障碍病因之一[3]。据信在美国一年会造成6,040亿美元的经济损失[2] 。失智症患者常因照护需要,其人身自由遭到物理性或化学约束,引发了人权议题的争论[2] ;患者也经常苦于因病遭遇污名化[3]。

症候及征象

编辑失智症的症状随著不同的诊断的类型和阶段而有所变异[27]。脑部最常被影响的区块为记忆、视觉空间感、语言、注意力,和解决问题的部分;多数失智症的类型多为缓慢渐进型式,当患者显现相关症状时,可能已持续经历长期的失智症脑部进展。同一患者也可能同时得到两种以上的失智症。约有10%失智症病人是混合型态的,通常会合并得到阿兹海默症和另一种失智症像是额颞叶型失智症或是血管性失智症。

失智症可能同时具备神经精神医学的症状,称为失智之行为精神症状(英语:Behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia,简称为 BPSD),兹列如下[28]:

所有失智症类型患者皆可能出现的行为及心理症状如下[30][31]:

当失智症患者遇到超乎其所能掌控之情况,易导致情绪改变之反应,如大哭或暴怒,也就是所谓“灾难性反应”(英语:catastrophic reaction)[32]。

期别

编辑轻度认知功能障碍(MCI)

编辑在失智症的第一阶段,疾病的症状和体征可能不易察觉。初期的失智症症状,常在确诊后回溯过往征兆时,才较为明朗。初期阶段称为轻度认知功能障碍,诊断为此阶段之患者中,近七成会进展为失智症[13]。虽然患者的脑部大多已有长期病变,然而尚未严重到影响患者的日常作息,其症状也才正开始显现;若症状已影响到患者的日常作息,诊断结果多已为失智症。患者的简短智能测验(简称 MMSE)分数仍会落在正常区间,大约27~30之间。患者可能会有部份记忆问题或遗忘某些词汇,但患者仍能解决日常生活所遇到的问题,也能妥善处理自己的生活起居[34]。

早期阶段

编辑失智症早期阶段,周遭亲友开始可意识到患者的症状。此外,患者症状亦开始干扰日常活动。早期阶段患者的简短智能测验,得分多介于20~25之间。阶段症状取决于失智症的类型。患者可能开始在从事较复杂家务或工作任务时遭遇困难。患者通常仍可照顾自己,但容易忘记服药或洗衣服等事情,可能需要提示或提醒[35]。

初期症状症状通常包括记忆障碍、唤词困难(失语症)及计划组织能力的功能性问题[36]。较有效地评估患者的退化情形,可透过询问患者能否独立处理自身财务,这也是患者首要常见的生活问题。其他常反映在生活中的现象,例如:在陌生区域迷路、重复行为或事件、性格改变、社交退缩和难以如常工作[37]。

当评估对象是否罹患失智症时,须将其 5~10 年内的行为能力状况,纳入考量重点;然而在评估对象行为能力是否耗损时,亦须将其教育程度也纳入考量。举例来说:再也无法计算帐务达收支平衡的会计师,与高中辍学者或从未关心财务者相比,前者较后者需要更多关注[13]。

阿兹海默症型失智症中,最显著的早期症状是记忆困难,其馀症状包括唤词困难(失语症)及容易迷路。其他种类如路易体失智症(Lewy bodies dementia)和额颞型失智症(fronto-temporal dementia)的早期病征,常见是性格改变,及计划组织能力的功能性问题。

中期阶段

编辑随著失智症之病程进展,初期显现症状会渐趋恶化,其衰退速度因人而异。中期阶段患者的简短智能测验,得分通常在6~17之间。举例而言,此阶段的阿兹海默症型失智症,在面对多数新接收资讯时,遗忘相当迅速。患者的解决问题能力可能会严重缺损,社交判断力亦会受影响。患者离家出外时的行为能力不足,平均而言不建议让患者单独行动。患者或许能在家中处理简单家务,但可能无法完成较复杂的任务。患者可能开始需要个人照护与卫生上的协助,而非简单的提醒或提示[13]。

晚期阶段

编辑晚期阶段的失智症患者常见会渐趋内向,且需要大范围或全职的个人照护,常需要全天候照护以确保其人身安全,并满足其日常基本需求。若无人照料,患者容易在外迷路游荡或跌倒,亦可能无法辨认日常环境中的危险因子,像是滚烫的火炉。患者不一定能意识到自己需要如厕,或无法控制自己的膀胱及肛门机能(即失禁)[34]。

晚期失智症阶段也常会影响患者饮食。照顾者为延长患者之生命,常会提供泥状食物和糊状饮品,使患者增加体重、避免噎到,亦让进食过程简单化,并协助进食[38]。病患食欲可能下降至不愿进食,亦可能不愿下床,或需要他人全力协助才能下床。一般而言,患者在此阶段不再能认出亲友。患者在睡眠习惯上常有重大改变,亦或难以入眠[13]。

病因

编辑可逆的病因

编辑有些类型的失智症在治疗后可以轻易恢复,例如甲状腺机能低下症,维生素B12缺乏症,莱姆病和神经性梅毒。 所有出现记忆障碍的人,都应检查甲状腺功能并排除B12缺乏症。对莱姆病和神经梅毒,若患者具有患病的危险因子,也应进行测试。但是否具有危险因子常常难以确定[39],因此,对怀疑患有失智症者进行进行神经梅毒、莱姆病以及其他上述检查,尚属必需[13]:31–32。听觉障碍也可能与失智症相互关联[40]。初步研究显示配带助听器可能有帮助。

阿兹海默症

编辑阿兹海默症占失智症总病例的50%至70%[2][3]。阿兹海默症最常见的症状是短期记忆丧失和单词提取困难。患有阿兹海默症的人在视觉空间区域(例如,他们可能开始常常迷路),推理、判断和洞察方面也存在问题。洞察力是指该人是否意识到自己存在记忆障碍。

阿兹海默症的常见早期症状包括重复行为(repetition)、迷路、财务处理困难,尤其是在做新的或复杂的饭菜时出现烹饪问题,忘记服药,或是单字回忆困难。

受阿兹海默症影响最大的大脑部分是海马体,大脑颞叶和顶叶也可能会出现萎缩情形[13]。这种顶颞型脑皮质萎缩很可能是阿兹海默症,但反之未必如此。阿兹海默症的大脑萎缩变化很大,单纯脑部断层扫描实际上无法做出诊断。麻醉与阿兹海默症病之间的关系尚不清楚[41]。

血管性失智症

编辑血管性失智症约占失智症患者的20%以上,是常见病因中的第二名[42]。血管性失智是因为疾病或是创伤,影响脑部的血液供应,一般是因为几次的轻微中风造成。血管性失智的症状会依中风影响的脑部部位,以及堵塞血管的大小而不同[13],多重的受伤可能会造成随时间恶化的失智症,而有关认知关键区域(例如海马体,丘脑)的单次受伤可能会造成突然的认知衰退[42]。

脑部断层扫描可以看出脑部不同部位多次中风的证据。有血管性失智的人也常会有血管性疾病的危险因子,例如吸烟、高血压、心房颤动、高胆固醇血症或,糖尿病,也可能有其他血管疾病的症状,例如以往可能也曾有心肌梗死或心绞痛。

路易氏体失智症

编辑路易氏体失智症的典型症状为视幻觉及帕金森症候群。帕金森氏症候群是帕金森氏症的症状集之一,症状包含震颤、肌肉僵硬,以及面无表情等等。路易氏体失智症的视幻觉内容多半是生动的人或动物,经常发生于患者即将入睡或刚醒来时。其他较突出的症状包含注意力不集中、组织企划与解决能力产生问题、以及视觉空间功能出现障碍等[13]。

在诊断路易氏体失智症时,只根据医学影像不足以进行诊断,不过还是有些特殊的症状。路易氏体失智大症患者在进行单光子电脑断层扫描(SPECT)时,后枕骨部位会有低灌流的情形,或是在正子断层照影时,后枕骨会有低代谢的症状。一般而言,路易氏体失智症会直接给予诊断,除非是较复杂的情形,不然多半不需要脑部影像[13]。

额颞型失智症

编辑额颞叶型失智症(Frontotemporal Dementia,FTD)的特点是剧烈的性格变化以及语言的困难。所有的额颞型失智症都有较早期的社交退缩,早期也不容易查觉是此一病症。此病症的主要症状不是记忆方面的问题[13][43]。

额颞叶型失智症共有六型。第一型的主要症状是在个性和行为上,称为行为变异型FTD(behavioral variant FTD,bv-FTD),也是最常见的一种。其症状包括个人卫生上的改变,思考的僵化,不过常常不会注意到这些症状。患者会有社交退缩及食欲的大幅增加。患者有时会有在社交上不恰当的举动,例如不恰当的性评论,或是开始公开的看色情的刊物或影片。其中最常见的症状是冷漠(Apathy),对任何事物都不关心,不过其他种类的失智症也常会有冷漠的症状[13]。

Two types of FTD feature aphasia (language problems) as the main symptom. One type is called semantic variant primary progressive aphasia (SV-PPA). The main feature of this is the loss of the meaning of words. It may begin with difficulty naming things. The person eventually may lose the meaning of objects as well. For example, a drawing of a bird, dog, and an airplane in someone with FTD may all appear almost the same.[13] In a classic test for this, a patient is shown a picture of a pyramid and below it a picture of both a palm tree and a pine tree. The person is asked to say which one goes best with the pyramid. In SV-PPA the person cannot answer that question. The other type is called non-fluent agrammatic variant primary progressive aphasia (NFA-PPA). This is mainly a problem with producing speech. They have trouble finding the right words, but mostly they have a difficulty coordinating the muscles they need to speak. Eventually, someone with NFA-PPA only uses one-syllable words or may become totally mute.

额颞叶型失智症中有两种的主要症状都是失语症。一种称为语义变异原发进行性失语症(semantic variant primary progressive aphasia、SV-PPA),主要特征是忘记词语的意思,一开始的症状是会弄混东西的名称,最后也会忘记东西的意思,例如此种失智症患者画的鸟、狗及飞机可能会几乎一模一样[11]。在相关的经典测试中,会给病患看金字塔的图片,其下方有棕榈树和松树的图片,问病患哪一种树会适合在金字塔附近出现,SV-PPA的患者会无法回答。另一种称为不流利语法变异原发进行性失语症(non-fluent agrammatic variant primary progressive aphasia、NFA-PPA),主要的症状是在说话时出现,此疾病的病患不容易找到正确的字,不过大部份的困难是在无法控制说话时需要用到的肌肉。最后有些NFA-PPA的患者只会用单字节的字,有些则不再说话。

Progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP) is a form of FTD that is characterized by problems with eye movements. Generally the problems begin with difficulty moving the eyes up or down (vertical gaze palsy). Since difficulty moving the eyes upward can sometimes happen in normal aging, problems with downward eye movements are the key in PSP. Other key symptoms include falling backward, balance problems, slow movements, rigid muscles, irritability, apathy, social withdrawal and depression. The person may have certain "frontal lobe" signs such as perseveration, a grasp reflex and utilization behavior (the need to use an object once you see it). People with PSP often have progressive difficulty eating and swallowing, and eventually with talking. Because of the rigidity and slow movements, PSP is sometimes misdiagnosed as Parkinson's disease. On scans the midbrain of people with PSP is generally shrunken (atrophied), but no other common brain abnormalities are visible.

渐进性核上性麻痹(PSP)也是额颞叶型失智症中的一种,特征是无法控制眼球的活动。一开始的问题多半是眼球上下移动的困难(垂直凝视麻痹),由于在一般的老化过程中,有时也会有眼球无法朝上动的问题,因此诊断PSP的关键是眼球无法往下移动。其他主要的症状包括往后跌倒、平衡问题、动作缓慢、肌肉僵硬、烦躁、冷漠、社交退缩和抑郁。此疾病的患者可能会有一些“额叶”症状,例如持续动作(perseveration)、抓握反射及使用行为(看到物体后一定要用该物体)。PSP的患者会渐进性的难以进食及吞咽,最后在说话上也有困难,因为PSP患者的肢体僵硬,而且动作缓慢,有时会误诊为帕金森氏症。在脑部扫描时会发现PSP患者的中脑萎缩,不过多半不会有其他的症状。

Corticobasal degeneration (CBD) is a rare form of FTD that is characterized by many different types of neurological problems that progressively worsen. This is because the disorder affects the brain in many different places, but at different rates. One common sign is difficulty with using only one limb. One symptom that is rare in any other condition is the "alien limb". The alien limb is a limb that seems to have a mind of its own, it moves without conscious control of the person's brain. Other common symptoms include jerky movements of one or more limbs (myoclonus), symptoms that are different in different limbs (asymmetric), difficulty with speech from inability to move the mouth muscles in a coordinated way, numbness and tingling of the limbs and neglecting one side of vision or senses. In neglect, a person ignores the opposite side of the body from the one that has the problem. For example, a person may not feel pain on one side, or may only draw half of a picture when asked. In addition, the person's affected limbs may be rigid or have muscle contractions causing dystonia (strange repetitive movements).[13] The brain area most often affected in corticobasal degeneration is the posterior frontal lobe and parietal lobe, although many other parts can be affected.[13]

皮质基底核退化症(Corticobasal degeneration,CBD)是罕见的额颞叶型失智症,特点是有几许多不同种类的神经问题,而且都会渐渐恶化。这是因为疾病会影响大脑不同的部位,而影响的速度也各有不同。其中一个常见的症状是只能活动一只手或是一只脚,另一种症状在其他疾病中很少见,称为“外星人肢体”(alien limb),是似乎有自己意志的肢体,会不受大脑控制,无意识的活动。另一个常见的症状包括一个或多个肢体的抽搐运动(肌阵挛),两侧肢体的症状不同(不对称),因为无法以协调的方式控制嘴部肌肉运动,因此无法说话,肢体麻痹或是刺痛,失去某一侧的视觉或是感觉。若有人无法感觉到身体的某一侧,可能就有此问题。例如,患者可能会感受不到身体某一侧的疼痛,或是在画图时只画了某半边的图。另外,受影响的肢体可能会僵硬或肌肉收缩,因此有肌张力障碍(奇怪的重复动作)[11]。最容易受到皮质基底核退化症影响的大脑部位为后额叶及顶叶,不过其他部位也常会受到影响[11]。

最后,额颞叶型失智症(FTD)也可能伴随著运动神经元疾病(Motor Neurone Disease),称为FTD-MDD。此类患者会同时有额颞叶型失智症的症状(行为、语言及活动问题,以及神经肌肉疾病的症状(运动神经元的死亡)。

快速进展性失智症

编辑Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease typically causes a dementia that worsens over weeks to months, and is caused by prions. The common causes of slowly progressive dementia also sometimes present with rapid progression: Alzheimer's disease, dementia with Lewy bodies, frontotemporal lobar degeneration (including corticobasal degeneration and progressive supranuclear palsy).

库贾氏病会造成的失智症多半会在几周到数个月内恶化,是由朊毒体引起。一般缓慢进展的失智症有时也会以快速进展的方式出现: 阿兹海默症、路易氏体失智症、额颞叶退化(包括皮质基底退化及 进行性核上性麻痹)。

Encephalopathy or delirium may develop relatively slowly and resemble dementia. Possible causes include brain infection (viral encephalitis, subacute sclerosing panencephalitis, Whipple's disease) or inflammation (limbic encephalitis, Hashimoto's encephalopathy, cerebral vasculitis); tumors such as lymphoma or glioma; drug toxicity (e.g., anticonvulsant drugs[需要明确引用]); metabolic causes such as liver failure or kidney failure; chronic subdural hematoma; and repeated brain trauma (chronic traumatic encephalopathy, a condition associated with contact sports).

另一方面,脑病或谵妄也可能发展的较慢,出现类似失智症的症状。可能的原因还包括脑部感染(病毒性脑炎、亚急性硬化性全脑炎、whipple氏病)或是发炎(边缘性脑炎、桥本脑病、脑血管炎),像是淋巴瘤或神经胶质瘤等肿瘤,药物毒性(例如抗惊厥药),或是代谢相关原因(例如肝性脑病、[]肾功能衰竭]]或慢性硬膜下血肿)。

免疫相关的失智症

编辑Chronic inflammatory conditions that may affect the brain and cognition include Behçet's disease, multiple sclerosis, sarcoidosis, Sjögren's syndrome, systemic lupus erythematosus, celiac disease, and non-celiac gluten sensitivity.[44][45] These types of dementias can rapidly progress, but usually have a good response to early treatment. This consists of immunomodulators or steroid administration, or in certain cases, the elimination of the causative agent.[45] A 2019 review found no association between celiac disease and dementia overall but a potential association with vascular dementia.[46] A 2018 review found a link between celiac disease or non-celiac gluten sensitivity and cognitive impairment and that celiac disease may be associated with Alzheimer's disease, vascular dementia, and frontotemporal dementia.[47] A strict gluten-free diet started early may protect against dementia associated with gluten-related disorders.[46][47]

会影响到脑部和认知状态的慢性发炎性疾病有贝赛特氏症、多发性硬化症、结节病、干燥综合症、全身性红斑狼疮、乳糜泻和非乳糜泻的麸质敏感[42][43]。这些型态的失智症可以进展快速,但通常早期治疗的效果很好。治疗种类有免疫治疗或类固醇,或在特殊状况下,可以移除影响的物质[43]。一篇2019的回顾性文章发现乳糜泻和失智症没有任何关联,但可能跟血管性痴呆有一点关联性[44]。一篇2018的回顾性文章发现乳糜泻或是非乳糜泻的麸质敏感跟认知功能受损有一点相关,也就是乳糜泻有可能跟阿兹海默症、血管性痴呆以及额颞叶型失智症有相关性[45]。尽早开始严格的无麸质饮食对于与麸质相关病症有关联的失智症可能会有改善[44][45]。

其他疾病

编辑Many other medical and neurological conditions include dementia only late in the illness. For example, a proportion of patients with Parkinson's disease develop dementia, though widely varying figures are quoted for this proportion.[48] When dementia occurs in Parkinson's disease, the underlying cause may be dementia with Lewy bodies or Alzheimer's disease, or both.[49] Cognitive impairment also occurs in the Parkinson-plus syndromes of progressive supranuclear palsy and corticobasal degeneration (and the same underlying pathology may cause the clinical syndromes of frontotemporal lobar degeneration). Although the acute porphyrias may cause episodes of confusion and psychiatric disturbance, dementia is a rare feature of these rare diseases. Limbic-predominant age-related TDP-43 encephalopathy (LATE) is a type of dementia that primarily affects people in their 80s or 90s and in which TDP-43 protein deposits in the limbic portion of the brain.[50]

有许多疾病和神经疾病在后期会有失智症的症状。例如帕金森氏症的患者中,有些会出现失智症,程度度各有不同[46]。若帕金森氏症伴随著失智症,根本病因可能是路易氏体失智症或阿兹海默症,也可能两者都有[47]。认知障碍也可能出现在进行性核上性麻痹和皮质基底突变性的病症中(和相同潜在病理可能导致额颞叶变性的临床症状)。急性紫质症会有精神错乱及精神疾病的症状,但很少会出现失智症的情形。边缘性为主的年龄相关性TDP-43脑病(LATE)也是失智症的一种,主要影响80至90岁的人,是脑部边缘系统中TDP-43蛋白质沉积的病症[48]。

Aside from those mentioned above, heritable conditions that can cause dementia (alongside other symptoms) include:[51]

除了上述疾病外,以下遗传性疾病也可能引起失智症[49]:

轻度认知障碍

编辑Mild cognitive impairment means that the person exhibits memory or thinking difficulties, but those difficulties are not severe enough for a diagnosis of dementia.[52] They should score between 25–30 on the MMSE.[13] Around 70% of people with MCI go on to develop some form of dementia.[13] MCI is generally divided into two categories. The first is primarily memory loss (amnestic MCI). The second is anything else (non-amnestic MCI). People with primarily memory problems typically develop Alzheimer's disease. People with the other type of MCI may develop other types of dementia.

轻度认知障碍(MCI)是指患者虽然出现记忆力或思考困难的症状,但程度尚未严重到可以被诊断为痴呆症的情形,[50]此类患者的MMSE测试得分会介于25-30之间[10],而约有70%的轻度认知障碍患者病情会持续演变成某些痴呆症。[10] 轻度认知障碍通常分为两类,第一类是主要记忆丧失(健忘型MCI),第二类是其他记忆丧失(非健忘型MCI)。罹有健忘型MCI的人常常会演变成阿尔海默症,而罹有非健忘型的MCI的人则可能会演变为其他种类的痴呆症。

Diagnosis of MCI is often difficult, as cognitive testing may be normal. Often, more in-depth neuropsychological testing is necessary to make the diagnosis. The most commonly used criteria are called the Peterson criteria and include:

- Memory or other cognitive (thought-processing) complaint by the person or a person who knows the patient well.

- A memory or other cognitive problem as compared to a person of the same age and level of education.

- Symptoms not severe enough to affect daily function.

- Absence of dementia.

要诊断轻度认知障碍并不容易,因为患者的认知功能测试结果可能与正常人无异,因此经常需要进行更深入的神经心理学测试才能确诊。目前最常使用的标准称为彼得森标准,内容包括:

- 患者自己或与患者熟识的人对患者的记忆力或其他认知(思维处理)功能的抱怨或投诉状况。

- 与相同年龄及教育水平的人相比之下,患者的记忆力或其他认知功能有无出现特别问题。

- 患者虽有出现症状,但不至于严重到影响日常生活。

- 尚未有失智症的症状。

固定型认知障碍

编辑Various types of brain injury may cause irreversible cognitive impairment that remains stable over time. Traumatic brain injury may cause generalized damage to the white matter of the brain (diffuse axonal injury), or more localized damage (as may also accompany neurosurgery). A temporary reduction in the brain's blood supply or oxygen may lead to hypoxic-ischemic injury. Strokes (ischemic stroke, or intracerebral, subarachnoid, subdural or extradural hemorrhage) or infections (meningitis or encephalitis) affecting the brain, prolonged epileptic seizures, and acute hydrocephalus may also have long-term effects on cognition. Excessive alcohol use may cause alcohol dementia, Wernicke's encephalopathy, or Korsakoff's psychosis.

许多类型的脑部损伤可能会导致无法回复的认知障碍,情况并会随著时间经过趋向固定。例如头部外伤(Traumatic brain injury, TBI)可能会对脑白质造成整体性的伤害(弥漫性轴索损伤),或者造成特定的局部损害(或因此需进行神经外科手术)。而大脑的血液或氧气供应若因故暂时减少,则可能会导致脑部产生缺氧或缺血性的伤害。再像是中风(例如缺血性中风、出血性中风、蛛网膜下腔出血、硬脑膜下出血或硬膜外出血等)及细菌或病毒感染(例如脑膜炎或脑炎)也都会影响脑部功能。此外,长时间的癫痫发作和急性脑积水也可能会对认知功能产生长期性的影响。至于过量饮酒则可能会导致酒精性失智症、韦尼克式氏脑病变(Wernicke's encephalopathy)或是高沙可夫症候群(Korsakoff's syndrome,和前者一样都是一种缺乏维生素B1引发的神经系统疾病)。

缓慢进展的失智症

编辑Dementia that begins gradually and worsens over several years is usually caused by neurodegenerative disease—that is, by conditions that affect only or primarily brain neurons and cause gradual but irreversible loss of function. Less commonly, a non-degenerative condition may have secondary effects on brain cells, which may or may not be reversible if the condition is treated.

若失智症是慢慢出现,在几年内恶化,一般是由神经退化障碍所造成的,也就是一些只影响脑神经(或是主要影响脑神经)的疾病,其机能会渐进式的丧失,但其影响是不可逆的。偶尔有些非退化性的疾病也会影响脑神经,若已治疗该疾病,脑神经的影响有些可逆,有些不可逆。

Causes of dementia depend on the age when symptoms begin. In the elderly population, a large majority of dementia cases are caused by Alzheimer's disease, vascular dementia, or dementia with Lewy bodies.[53][54][55] Hypothyroidism sometimes causes slowly progressive cognitive impairment as the main symptom, which may be fully reversible with treatment. Normal pressure hydrocephalus, though relatively rare, is important to recognize since treatment may prevent progression and improve other symptoms of the condition. However, significant cognitive improvement is unusual.

失智症的病因和症状开始时的年龄有关。若是年龄较长的病患,大部份的失智症是因为阿兹海默症、血管性失智症或路易氏体失智症[51][52][53]。有时甲状腺机能低下症也会有缓慢进展的认知障碍,在治疗后,其认知障碍的影响是完全可逆的。常压性水脑症相当少见,但若治疗,可以预防失智症的进展,也可乆改善此病症的其他症状,只是不太容易有显著的改善。

Dementia is much less common under 65 years of age. Alzheimer's disease is still the most frequent cause, but inherited forms of the disorder account for a higher proportion of cases in this age group. 额颞叶变性 and Huntington's disease account for most of the remaining cases.[56] Vascular dementia also occurs, but this in turn may be due to underlying conditions (including antiphospholipid syndrome, CADASIL, MELAS, homocystinuria, moyamoya, and Binswanger's disease). People who receive frequent head trauma, such as boxers or football players, are at risk of chronic traumatic encephalopathy[57] (also called dementia pugilistica in boxers).

65岁以下的人罹患失智症的比例就少很多。阿兹海默症仍是最常见的病因,不过遗传类的疾病也占了相当的比例,最常见的是额颞叶变性及亨丁顿舞蹈症[54]。也有血管性失智症的情形,火过也可能是因为其他潜藏的病因造成(例如抗磷脂症候群、体显性脑动脉血管病变合并皮质下脑梗塞及脑白质病变、乳酸血症及类中风症状、高胱胺酸尿症、毛毛样血管疾病及宾斯旺格病)。若是头部常受创伤的人,例如拳击手或是美式足球员,其患有慢性创伤性脑病变的风险较高[55]。对于拳击手而言,也称为拳击手失智(dementia pugilistica)。

In young adults (up to 40 years of age) who were previously of normal intelligence, it is very rare to develop dementia without other features of neurological disease, or without features of disease elsewhere in the body. Most cases of progressive cognitive disturbance in this age group are caused by psychiatric illness, alcohol or other drugs, or metabolic disturbance. However, certain genetic disorders can cause true neurodegenerative dementia at this age. These include familial Alzheimer's disease, SCA17 (dominant inheritance); adrenoleukodystrophy (X-linked); Gaucher's disease type 3, metachromatic leukodystrophy, Niemann-Pick disease type C, pantothenate kinase-associated neurodegeneration, Tay–Sachs disease, and Wilson's disease (all recessive). Wilson's disease is particularly important since cognition can improve with treatment.

若发生失智症的是四十岁以下的青年,且之前的智力正常,绝大多数是因为其他神经疾病,或是身体其他部份的疾病所造成的。此年龄层会有渐进型认知障碍的主要原因是为精神疾病、使用酒精或是其他药物、或是代谢性疾病。不过有些遗传性疾病会在此年龄层产生真正的神经退化性失智,这些疾病包括早发性阿兹海默症、小脑萎缩症(显性基因)、肾上腺脑白质失养症(X染色体的伴性遗传)、高雪氏症第三型、异染性脑白质退化症、C型尼曼匹克氏症、泛酸激酶相关的神经变性、Tay-sachs疾病,及肝豆状核变性(都是隐性基因)。肝豆状核变性特别值得注意,因为治疗后认知会有一些改善。

At all ages, a substantial proportion of patients who complain of memory difficulty or other cognitive symptoms have depression rather than a neurodegenerative disease. Vitamin deficiencies and chronic infections may also occur at any age; they usually cause other symptoms before dementia occurs, but occasionally mimic degenerative dementia. These include deficiencies of vitamin B12, folate, or niacin, and infective causes including cryptococcal meningitis, AIDS, Lyme disease, progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy, subacute sclerosing panencephalitis, syphilis, and Whipple's disease.

不论是哪个年龄层,有记忆困难或是其他认知症状的人当中,有一定比例是因为重性抑郁疾患而造成此症状。维生素不足及慢性感染在任何年龄层都可能出现,一般在出现失智症状前,会有其他的症状,不过偶尔也会有类似失智症的症状。这类维生素不足疾病有维生素B12缺乏症、叶酸缺乏症及糙皮病,感染性疾病有[[隐球菌病、AIDS、莱姆病、进行性多灶性白质脑病、亚急性硬化性全脑炎、梅毒及鞭毛病。

边缘性为主的年龄相关性TDP-43脑病

编辑Limbic-predominant age-related TDP-43 encephalopathy (LATE) is a type of dementia similar to Alzheimer disease which was proposed in 2019.[58] Usually older people are affected.[58]

边缘性为主的年龄相关性TDP-43脑病(LATE)是类似阿兹海默症的失智症,在2019年发现的[54]。一般是较年长者容易患病[54]。

听觉障碍

编辑Hearing loss is linked with dementia with a greater degree of hearing loss tied to a higher risk.[40] One hypothesis is that as hearing loss increases, cognitive resources are redistributed to auditory perception to the detriment of other cognitive processes.[40] Another hypothesis is that hearing loss leads to social isolation which negatively affect the cognitive functions.[40]

听觉障碍和失智症有关,听觉障碍的程度越严重,失智症的风险越高[36]。有种假说认为在听觉障碍变严重时,人体会将认知资源重新调整到听觉,因此造成其他认知功能的恶化[36]。另一种假说是听觉障碍会造成社交孤立,对认知功能有负面影响[36]。

混合型失智症

编辑失智症的患者中,约有10%的病人为混合型失智症(mixed dementia),多半是结合阿兹海默症和其他种类的失智症(如额颞叶型失智症或血管性失智症等)[59][60]。

诊断

编辑Symptoms are similar across dementia types and it is difficult to diagnose by symptoms alone. Diagnosis may be aided by brain scanning techniques. In many cases, the diagnosis requires a brain biopsy to become final, but this is rarely recommended (though it can be performed at autopsy). In those who are getting older, general screening for cognitive impairment using cognitive testing or early diagnosis of dementia has not been shown to improve outcomes.[61] However, screening exams are useful in 65+ persons with memory complaints.[13]

不同的失智症的症状表现往往相似,因此单纯从症状来诊断失智症是很困难的。诊断的方法可以纳入神经成像的技术。在很多案例中,需要大脑活体组织切片才能确定诊断,但这个方法罕有人推荐(虽然可以验尸)。在年纪增长的人们中,用认知检测工具来筛检认知功能衰退者或是早期诊断失智症者并没有显示有改善预后[59]。然而,筛检工具对于65岁以上并且有记忆问题的老年人们是有帮助的[10]。

Normally, symptoms must be present for at least six months to support a diagnosis.[62] Cognitive dysfunction of shorter duration is called delirium. Delirium can be easily confused with dementia due to similar symptoms. Delirium is characterized by a sudden onset, fluctuating course, a short duration (often lasting from hours to weeks), and is primarily related to a somatic (or medical) disturbance. In comparison, dementia has typically a long, slow onset (except in the cases of a stroke or trauma), slow decline of mental functioning, as well as a longer trajectory (from months to years).[63]

正常来说,要下诊断前症状必须持续表现至少六个月[60]。短时间的认知功能缺损称为谵妄。谵妄和失智症常常会因为相似的症状而被混淆。谵妄通常是有一个快速的发作、高低起伏的过程、短的持续时间(多半是持续几小时到几周)和多跟身体混乱或医疗状态有关。相比之下,失智症典型是有长的持续时间、缓慢的发作型态(除了中风或创伤造成的失智症以外)、心智功能缓慢的下降,和相对较长的过程(几个月到几年)[61]。

Some mental illnesses, including depression and psychosis, may produce symptoms that must be differentiated from both delirium and dementia.[64] Therefore, any dementia evaluation should include a depression screening such as the Neuropsychiatric Inventory or the Geriatric Depression Scale.[13] Physicians used to think that people with memory complaints had depression and not dementia (because they thought that those with dementia are generally unaware of their memory problems). This is called pseudodementia. However, in recent years researchers have realized that many older people with memory complaints in fact have MCI, the earliest stage of dementia. Depression should always remain high on the list of possibilities, however, for an elderly person with memory trouble.

一些精神疾患包含抑郁和思觉失调可能会表现出一些类似的症状,需要跟谵妄和失智症表现出的症状做鉴别诊断[62]。因此,任何对失智症的评估都应该要包含一个对抑郁症的筛检,像是神经精神评估量表或是老年忧郁量表[10]。医生们过去认为会提到自己有记忆问题的患者通常是患有抑郁症而非失智症(因为医生们认为患有失智症者多半会不知道自己有记忆问题)。这以往被叫做伪失智症。然而,在最近几年,研究者发现到许多自诉有记忆问题的老年人实际上患有MCI,也就是最刚开始阶段的失智症。虽说如此,但在有记忆问题的年长者身上还是不能太快排除抑郁症的可能性。

Changes in thinking, hearing and vision are associated with normal ageing and can cause problems when diagnosing dementia due to the similarities.[65]

思考、听力和视觉的改变可以是正常老化的影响,但相似于失智症的表现也就造成诊断失智症一定的困难[63]。

认知检测

编辑| Test | Sensitivity | Specificity | Reference |

| MMSE | 71%–92% | 56%–96% | [66] |

| 3MS | 83%–93.5% | 85%–90% | [67] |

| AMTS | 73%–100% | 71%–100% | [67] |

Various brief tests (5–15 minutes) have reasonable reliability to screen for dementia. While many tests have been studied,[68][69][70] presently the mini mental state examination (MMSE) is the best studied and most commonly used. The MMSE is a useful tool for helping to diagnose dementia if the results are interpreted along with an assessment of a person's personality, their ability to perform activities of daily living, and their behaviour.[71] Other cognitive tests include the abbreviated mental test score (AMTS), the, Modified Mini-Mental State Examination (3MS),[72] the Cognitive Abilities Screening Instrument (CASI),[73] the Trail-making test,[74] and the clock drawing test.[75] The MoCA (Montreal Cognitive Assessment) is a reliable screening test and is available online for free in 35 different languages.[13] The MoCA has also been shown somewhat better at detecting mild cognitive impairment than the MMSE.[76][77]Brief cognitive tests may be affected by factors such as age, education and ethnicity.[78]

| 检测 | 灵敏度 | 特异度 | 参考资料 |

| MMSE | 71%–92% | 56%–96% | [62] |

| 3MS | 83%–93.5% | 85%–90% | [63] |

| AMTS | 73%–100% | 71%–100% | [63] |

许多简短(5至15分钟)的检测在筛检失智症上有不错的可靠度。已针对许多的检测进行研究[64][65][66],其中简短智能测验(MMSE)是研究效果最好,也是最常使用的测验。假如MMSE的结果可以配合个人的人格特质、进行日常行为的能力及行为评估来进行诠释,MMSE是有效诊断失智症的工具。其他认知测验的工具包括简短智力检测量表(AMTS)、修正简短心智量表(3MSE)[68]、认知筛检测验(CASI)[69]、路径描绘测验[70]以及画时钟测验(clock drawing test)[71]。蒙特利尔认知评估(MoCA)是可以筛检失智症的可靠工具,已有35种语言的线上免费版本[10]。在检测轻微的认知障碍时,MoCA某些方面的效果比MMSE要好[72][73]。简短的认知测验可能会受到年龄、教育或是民族等因素的影响[74]。

Another approach to screening for dementia is to ask an informant (relative or other supporter) to fill out a questionnaire about the person's everyday cognitive functioning. Informant questionnaires provide complementary information to brief cognitive tests. Probably the best known questionnaire of this sort is the Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly (IQCODE).[79] Evidence is insufficient to determine how accurate the IQCODE is for diagnosing or predicting dementia.[80] The Alzheimer's Disease Caregiver Questionnaire is another tool. It is about 90% accurate for Alzheimer's when by a caregiver.[13] The General Practitioner Assessment Of Cognition combines both a patient assessment and an informant interview. It was specifically designed for use in the primary care setting.

另一种筛检失智症的方式是询问可提供患者资讯的人(亲友或是照顾者),来填写患者日常认知功能的问卷。这类的问卷会补充简短认知测验的资讯。这类问卷中最好的可能是老年人认知能力下降的调查问卷 (IQCODE)[75]。在诊断或预测失智症上,目前还没有足够资讯确认IQCODE的准确性[76]。另一个工具是阿兹海默症照顾者问卷(Alzheimer's Disease Caregiver Questionnaire),若由照顾者填写的话,侦测阿兹海默症约有90%的准确度[10]。全科医生认知评估结合了病患评估以及和资讯提供者的会谈。此问卷特别设计用在初级医疗的情境中。

Clinical neuropsychologists provide diagnostic consultation following administration of a full battery of cognitive testing, often lasting several hours, to determine functional patterns of decline associated with varying types of dementia. Tests of memory, executive function, processing speed, attention and language skills are relevant, as well as tests of emotional and psychological adjustment. These tests assist with ruling out other etiologies and determining relative cognitive decline over time or from estimates of prior cognitive abilities.

临床神经心理学家会在诊断协谈后进行一连串的认知测验,来确认不同类型失智症的功能衰退模式,测验大约需要几个小时,内容包括相关的记忆力、执行功能、处理速度、注意力以及语言能力,也会有情绪及心理调整功能的测试。这些测试可以排除其他的病因,也可以确认其他随时间进展的认知退化,及排除之前估计的认知异常。

Instead of using “mild or early stage”, “middle stage”, and “late stage” dementia as descriptors, numeric scales allow more detailed descriptions. These scales include: Global Deterioration Scale for Assessment of Primary Degenerative Dementia (GDS or Reisberg Scale),[81] Functional Assessment Staging Test (FAST),[82] and Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR).

描述失智症时,可以用初期、中期、末期的叙述,使用数字的量表可以提供更多的资讯。这些量表包括评估原发性退化性失智症的整体恶化量表(Global Deterioration Scale for Assessment of Primary Degenerative Dementia,简称GDS)或称为Reisberg量表[77]、功能评估分期测试(Functional Assessment Staging Test、简称FAST)[78]以及临床失智症分级(CDR)。

血液检查

编辑Routine blood tests are usually performed to rule out treatable causes. These tests include vitamin B12, folic acid, thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), C-reactive protein, full blood count, electrolytes, calcium, renal function, and liver enzymes. Abnormalities may suggest vitamin deficiency, infection, or other problems that commonly cause confusion or disorientation in the elderly.[来源请求]

可以用常规的 血液检查来排除一些可以治疗的病例,这些测试包括维生素B12、叶酸、促甲状腺激素 (TSH)、 C反应蛋白、全血细胞计数、电解质、钙质、肾功能及肝功能测试。异常可能是因为维生素缺乏症、感染、或是其他常见造成年长者混乱或方向感障碍的症状[来源请求]。

医学影像检测

编辑A CT scan or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI scan) is commonly performed, although these tests do not pick up diffuse metabolic changes associated with dementia in a person who shows no gross neurological problems (such as paralysis or weakness) on a neurological exam.[来源请求] CT or MRI may suggest normal pressure hydrocephalus, a potentially reversible cause of dementia, and can yield information relevant to other types of dementia, such as infarction (stroke) that would point at a vascular type of dementia.

诊断失智症时,常会进行断层扫描与核磁共振成像,虽然这两项医学测试若针对在神经系统检查中正常,没有神经系统问题(例如麻痹或虚弱)的人,无法检查出和失智病有关有关的弥散性代谢变化[来源请求]。断层扫描与核磁共振成像建议用于常压性水脑症,此症状可能会导致可逆性的失智症。同时断层扫描与核磁共振成像也可提供其他类型的失智症影像证据,例如血管梗塞(中风)可能会造成血管性失智症。

The functional neuroimaging modalities of SPECT and PET are more useful in assessing long-standing cognitive dysfunction, since they have shown similar ability to diagnose dementia as a clinical exam and cognitive testing.[83] The ability of SPECT to differentiate the vascular cause (i.e., multi-infarct dementia) from Alzheimer's disease dementias, appears superior to differentiation by clinical exam.[84]

单光子发射计算机断层成像术(SPECT)及正子断层照影(PET)的功能性神经影像学在诊断失智症上的效果和临床测试以及认知测试的效果相近,在评估长期的认知功能障碍时更加有效[79]。SPECT在区分血管性失智症(例如多发性梗塞性失智)以及阿兹海默症时,可以比临床测试更早区分这二种病症[80]。

Recent research has established the value of PET imaging using carbon-11 Pittsburgh Compound B as a radiotracer (PIB-PET) in predictive diagnosis, particularly Alzheimer's disease. Studies reported that PIB-PET was 86% accurate in predicting which patients with mild cognitive impairment would develop Alzheimer's disease within two years. In another study, carried out using 66 patients, PET studies using either PIB or another radiotracer, carbon-11 dihydrotetrabenazine (DTBZ), led to more accurate diagnosis for more than one-fourth of patients with mild cognitive impairment or mild dementia.[85]

最近的研究发现利用碳-11匹兹堡化合物B的正子断层照影(PIB-PET)在预测性诊断上的价值,特别是针对阿兹海默症。研究指出若是预测轻微认知障碍的患者在二年内出现阿兹海默症的机率,用 PIB-PET有86%的准确度。另一个研究针对66位患者的PET研究,使用PIB以及碳-11的dihydrotetrabenazine(DTBZ)比较,结果在轻微认知障碍或是轻微失智的诊断上,准确度要高25%[81]。

预防

编辑Various factors can decrease the risk of dementia.[86] As a group they may be able to prevent a third of cases. The group includes early education, treating high blood pressure, preventing obesity, preventing hearing loss, treating depression, physical activity, preventing diabetes, not smoking, and social connection.[86][87] The decreased risk with a healthy lifestyle is seen even in those with a high genetic risk.[88] A 2018 review however concluded that no medications have good evidence of a preventive effect, including blood pressure medications.[89]

许多方式都可以降低失智症的风险[5],若一起使用,可能可以减少三分之一的病例。这些方式包括早期教育、治疗高血压、避免肥胖、糖尿病及听觉障碍、治疗抑郁症、增加身体活动量、不要吸烟,以及增加和其他人的 社交连结[5][82]。较健康的生活方式可以减少风险,就算是遗传风险较高的人也可以看到效果[83]。不过2018年的回顾研究指出,没有哪一种医疗的预防效果有良好的文献支持,包括控制血压在内[84]。

Among otherwise healthy older people, computerized cognitive training may improve memory. However it is not known whether it prevents dementia.[90][91] Exercise has poor evidence of preventing dementia.[92][93] In those with normal mental function evidence for medications is poor.[94] The same applies to supplements.[95]

针对没有失智症症状的年长者,电脑化的认知训练可以提升记忆力,但不确定是否可以预防失智症[85][86]。找不到运动可以预防失智症的证据[87][88]。针对心智正常的年长者,有关药物预防失智的效果,缺乏足支支持的证据[89],营养补充品的情形也类似[90]。

The early introduction of a strict gluten-free diet in people with celiac disease or non-celiac gluten sensitivity before cognitive impairment begins potentially has a protective effect.[46]

若是有乳糜泻或是非乳糜泻的麸质敏感的人,在其出现认知障碍之前提早采用严格的无麸质饮食,可能会有保护作用,使其比较不容易罹患失智症[42]。

治疗

编辑Except for the treatable types listed above, no cure has been developed. Cholinesterase inhibitors are often used early in the disorder course; however, benefit is generally small.[9][96] Treatments other than medication appear to be better for agitation and aggression than medication.[97] Cognitive and behavioral interventions may be appropriate. Some evidence suggests that education and support for the person with dementia, as well as caregivers and family members, improves outcomes.[98] Exercise programs are beneficial with respect to activities of daily living and potentially improve dementia.[20]

除了上述所列可治疗类型的失智症外,其馀失智症则尚未发现任何治愈方式。乙酰胆碱酯酶抑制剂(Acetylcholinesterase inhibitor)通常会用于治疗早期症状,但大多只有轻微疗效[7][91]。对于患者出现的燥动不安和侵略性行为,药物以外的治疗方式似乎较为有效[92]。视情形有时也需要适当的介入以控制患者的认知和行为。某些证据显示,同时提供痴呆症患者、照顾者及家属相关的卫教及各种支援将有助于患者的病况[93]。制定运动菜单对患者的日常活动会有助益,且有潜力改善症状[17]。

心理治疗

编辑Psychological therapies for dementia include some limited evidence for reminiscence therapy (namely, some positive effects in the areas of quality of life, cognition, communication and mood – the first three particularly in care home settings),[99] some benefit for cognitive reframing for caretakers,[100] unclear evidence for validation therapy[101] and tentative evidence for mental exercises, such as cognitive stimulation programs for people with mild to moderate dementia.[102] Reminiscence therapy can improve quality of life, cognition, communication and possibly mood in people with dementia in some circumstances, although all of these benefits may be small.[99]

失智症的心理治疗包括证据还不太足份的怀旧疗法(以其名称来看,是一些在生活品质、认知、沟通以及情绪上的一些正面效果,在家庭护理环境中,格外重视前三项)[94],可能有些帮助,针对照顾者的认知重新框架[95],还没有清楚证据的确认疗法[96],以及有初步证据的心智锻炼,像是针对轻微到中度失智症的认知刺激计划[97]。怀旧疗法可以提升失智症在一些环境下的生活品质、认知、沟通,也可能对情绪有帮助,不过这些的效果都很小[94]。

Adult daycare centers as well as special care units in nursing homes often provide specialized care for dementia patients. Adult daycare centers offer supervision, recreation, meals, and limited health care to participants, as well as providing respite for caregivers. In addition, home care can provide one-on-one support and care in the home allowing for more individualized attention that is needed as the disorder progresses. Psychiatric nurses can make a distinctive contribution to people's mental health.[103]

成人日托中心以及疗养院中的特殊护理单位可以提到失智症患者的特殊照顾。成人日托中心可以提供监督,娱乐,进餐和一定程度的医疗保健,也是给照顾者的喘息机会。而且居家照护可以在家中提到一对一的支持以及照顾,随著病情的进展,可以有更多个人化的个性化护理。精神科的护理师可以对病患的心理健康作出独特的贡献[98]。

Since dementia impairs normal communication due to changes in receptive and expressive language, as well as the ability to plan and problem solve, agitated behaviour is often a form of communication for the person with dementia. Actively searching for a potential cause, such as pain, physical illness, or overstimulation can be helpful in reducing agitation.[104] Additionally, using an "ABC analysis of behaviour" can be a useful tool for understanding behavior in people with dementia. It involves looking at the antecedents (A), behavior (B), and consequences (C) associated with an event to help define the problem and prevent further incidents that may arise if the person's needs are misunderstood.[105] The strongest evidence for non-pharmacological therapies for the management of changed behaviours in dementia is for using such approaches.[106] Low quality evidence suggests that regular (at least five sessions of) music therapy may help institutionalized residents. It may reduce depressive symptoms and improve overall behaviour. It may also supply a beneficial effect on emotional well-being and quality of life, as well as reduce anxiety.[107] In 2003, The Alzheimer’s Society established 'Singing for the Brain' (SftB) a project based on pilot studies which suggested that the activity encouraged participation and facilitated the learning of new songs. The sessions combine aspects of reminiscence therapy and music. [108]

由于失智症患者接收语言及表达的能力改变,其日常沟通的能力退化,而计划及解决问题的能力也受到影响,躁动行动常常是失智症患者的一种沟通方式。主动的找寻其潜在原因(可能是疼痛、身体疾病或是过度刺激)可能可以减轻其躁动情形[99]。另外,“ABC行为分析”(ABC analysis of behaviour)是分析失智症患者行为的有效工具,其作法是分析一个事件有关的前因(antecedents,A)、行为(behavior, B)及结果(consequences,C),有助于定义其问题,并且可避免在患者需求被误解时,可能衍生的问题[100]。目前在针对失智症行为调整的非药物治疗中,具有最有力证据的就是使用此方式的研究[101]。有研究指出规律性(至少五次)的音乐治疗可能会对住院病患有帮助,可以减少忧郁症状,并提升整体行为,也对于情绪健康以及生活品质有正面的影响,也可以降低焦虑。不过证据品质不高[102]。阿兹海默症学会在2003年推动了Singing for the Brain(SftB)的前导研究计划,建议在活动中鼓励参与者学习新歌。此治疗方式结合了怀旧疗法以及音乐治疗[103]。

Some London hospitals found that using color, designs, pictures and lights helped people with dementia adjust to being at the hospital. These adjustments to the layout of the dementia wings at these hospitals helped patients by preventing confusion.[109]

有一些英国的医院发现改造病床与环境风格可以帮助失智症住院患者适应,包含配色、设计、海报图片与光线等方式。而利用旧照片、旧电影、旧家俱等复古装饰有助于减少失智症患者的困惑与焦虑。[102]<nowiki>

药物治疗

编辑No medications have been shown to prevent or cure dementia.[110] Medications may be used to treat the behavioural and cognitive symptoms, but have no effect on the underlying disease process.[13][111]

没有药物能够预防或治疗失智症[101]。虽然药物可以用于治疗行为和认知上的症状,不过对潜在的疾病进程没有影响[11][102]。

Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors, such as donepezil, may be useful for Alzheimer disease[112] and dementia in Parkinson's, DLB, or vascular dementia.[111] The quality of the evidence is poor[113] and the benefit is small.[9] No difference has been shown between the agents in this family.[18] In a minority of people side effects include a slow heart rate and fainting.[114]

乙酰胆碱酯酶抑制剂(例如多奈哌齐),可能对阿兹海默症[103]、帕金森氏症、路易氏体失智症和血管性失智症有所帮助[102]。然而该证据的质量并不是那么好[104],效益也不大[8]。在少数群体中副作用包含心跳过缓以及昏厥[105]。

As assessment for an underlying cause of the behavior is needed before prescribing antipsychotic medication for symptoms of dementia.[115] Antipsychotic drugs should be used to treat dementia only if non-drug therapies have not worked, and the person's actions threaten themselves or others.[116][117][118][119] Aggressive behavior changes are sometimes the result of other solvable problems, that could make treatment with antipsychotics unnecessary.[116] Because people with dementia can be aggressive, resistant to their treatment, and otherwise disruptive, sometimes antipsychotic drugs are considered as a therapy in response.[116] These drugs have risky adverse effects, including increasing the person's chance of stroke and death.[116] Given these adverse events and small benefit antipsychotics should be avoided whenever possible.[106] Generally, stopping antipsychotics for people with dementia does not cause problems, even in those who have been on them a long time.[120]

在开立抗精神病药物治疗失智症症状前,需评估造成症状的病因[106]。只有在非药物治疗对失智症患者无效,而且其行为威胁到自身或他人时,才能用抗精神病药物进行治疗[107][108][109][110]。激烈的行为改变,也有可能是其他可治疗疾病所造成,若是这样,其实不用抗精神病药物治疗[107]。由于有些失智症患者可能有攻击性,有破坏力,而且会抗拒治疗,有时会将抗精神病药物视为治疗方式之一[107]。抗精神病药物有危险性的不良反应,会增加中风及死亡的机率[107]。考虑抗精神病药物的不良反应及较小的益处,若可能的话,尽量避免使用这类药物[99]。一般而言,服用抗精神病药物的失智症病患停药不会有副作用,就算是长期服药的患者也是如此[111]。

N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor blockers such as memantine may be of benefit but the evidence is less conclusive than for AChEIs.[121] Due to their differing mechanisms of action memantine and acetylcholinesterase inhibitors can be used in combination however the benefit is slight.[122][123]

N-甲基-D-天门冬胺酸受体阻抗剂(像是美金刚)对失智症可能有效,但其证据效果没有AChEI要好[112]。由于这两种药物的作用机制不同,因此可以同时使用,不过助益不大[113][114]。

While depression is frequently associated with dementia, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) do not appear to affect outcomes.[124][125] The SSRIs sertraline and citalopram have been demonstrated to reduce symptoms of agitation, compared to placebo.[126]

虽然重度抑郁症常伴随失智症一起出现,但治疗重度抑郁症的选择性5-羟色胺再摄取抑制剂(SSRI)对失智症的症状改善不大[115][116]。SSRI中的舍曲林(sertraline)和西肽普兰(citalopram)已确认可以降低躁动的症状,效果比安慰剂要好[117]。

The use of medications to alleviate sleep disturbances that people with dementia often experience has not been well researched, even for medications that are commonly prescribed.[127] In 2012 the American Geriatrics Society recommended that benzodiazepines such as diazepam, and non-benzodiazepine hypnotics, be avoided for people with dementia due to the risks of increased cognitive impairment and falls.[128] Additionally, little evidence supports the effectiveness of benzodiazepines in this population.[127][129] No clear evidence shows that melatonin or ramelteon improves sleep for people with dementia due to Alzheimer's.[127] Limited evidence suggests that a low dose of trazodone may improve sleep, however more research is needed.[127]

关于使用药物改善失智症患者睡眠品质的策略,即使是常用的药物,目前也尚无足够研究[118]。2012年美国老年医学会建议苯二氮䓬类(BZD)安眠药物,如地西泮(Diazepam)等,应避免使用,因为这些药物可能会增加认知功能损伤的风险[119]。此外,目前也尚无足够实证支持此类药物对于此类患者的疗效[118][120]。目前尚无足够实证证明褪黑素或柔速瑞(ramelteon)能改善阿兹海默症的睡眠品质[118]。有薄弱证据显示曲唑酮可能可以改善睡眠症状,但仍需进一步研究[118]。

No solid evidence indicates that folate or vitamin B12 improves outcomes in those with cognitive problems.[130] Statins have no benefit in dementia.[131] Medications for other health conditions may need to be managed differently for a person who has a dementia diagnosis. It is unclear whether blood pressure medication and dementia are linked. People may experience an increase in cardiovascular-related events if these medications are withdrawn.[132]

目前尚无足够实证支持叶酸或维生素B12能改善认知问题[121]。他汀类药物(Statins)对于失智症也没有效益。失智症患者若同时患有其他疾病,必须斟酌调整药物。目前失智症与血压药之间的关联性尚不清楚。但目前认为停掉这些药物可能会增加心血管疾病的风险[123]。

The Medication Appropriateness Tool for Comorbid Health Conditions in Dementia (MATCH-D) criteria can help identify ways that a diagnosis of dementia changes medication management for other health conditions.[133] These criteria were developed because people with dementia live with an average of five other chronic diseases, which are often managed with medications.

平均每位失智症患者都罹患有其他五种慢性疾病,因此常并用其他药物。失智症患者共病药物使用适当性(MATCH-D)可以协助医事人员在处理失智症患者的共病时,可如何调整药物[124]。

疼痛

编辑As people age, they experience more health problems, and most health problems associated with aging carry a substantial burden of pain; therefore, between 25% and 50% of older adults experience persistent pain. Seniors with dementia experience the same prevalence of conditions likely to cause pain as seniors without dementia.[134] Pain is often overlooked in older adults and, when screened for, is often poorly assessed, especially among those with dementia, since they become incapable of informing others of their pain.[134][135] Beyond the issue of humane care, unrelieved pain has functional implications. Persistent pain can lead to decreased ambulation, depressed mood, sleep disturbances, impaired appetite, and exacerbation of cognitive impairment[135] and pain-related interference with activity is a factor contributing to falls in the elderly.[134][136]

随著年龄增长,成年人会遇到愈来愈多的健康问题,而且大部分的问题都会导致相当程度的疼痛;因此,有25%至50%的年长者平时会不断感到疼痛。而老年痴呆症患者出现疼痛情形的机率也与正常人一样[129] [129] [130]。老年人的疼痛问题常常被忽略,就算有进行监测,但疼痛评估的品质也往往不佳。对于痴呆症的患者的疼痛评估品质尤其低下,因为他们已无法告诉其他人他们的疼痛状况如何[129] [130]。除了人道关怀问题之外,持续无法缓解的疼痛更会为患者日常生活带来实际影响,造成包括活动力下降、情绪低落、睡眠障碍、食欲不振以及认知障碍恶化等问题[130],且因为疼痛造成的肢体活动不顺也是导致老年人跌倒的因素之一[129] [131]。

Although persistent pain in people with dementia is difficult to communicate, diagnose, and treat, failure to address persistent pain has profound functional, psychosocial and quality of life implications for this vulnerable population. Health professionals often lack the skills and usually lack the time needed to recognize, accurately assess and adequately monitor pain in people with dementia.[134][137] Family members and friends can make a valuable contribution to the care of a person with dementia by learning to recognize and assess their pain. Educational resources (such as the Understand Pain and Dementia tutorial) and observational assessment tools are available.[134][138][139]

尽管痴呆症患者的持续性疼痛难以传达、诊断和治疗,但若不去解决,将对已经是弱势的他们造成更严重的身心及生活品质上的影响。医护专业人员通常没时间,也缺乏技巧去识别、准确评估和充分监测痴呆症患者遭受的疼痛,[129] [132],但家人和朋友则可以借由学习如何识别及评估患者的痛苦,从而为照顾患者做出宝贵贡献;目前也已有提供相关教育资源(例如“了解疼痛与痴呆症”课程)及观察评估工具可使学习及使用[129] [133] [134]。

进食困难

编辑Persons with dementia may have difficulty eating. Whenever it is available as an option, the recommended response to eating problems is having a caretaker assist them.[116] A secondary option for people who cannot swallow effectively is to consider gastrostomy feeding tube placement as a way to give nutrition. However, in bringing comfort and maintaining functional status while lowering risk of aspiration pneumonia and death, assistance with oral feeding is at least as good as tube feeding.[116][140] Tube-feeding is associated with agitation, increased use of physical and chemical restraints and worsening pressure ulcers. Tube feedings may cause fluid overload, diarrhea, abdominal pain, local complications, less human interaction and may increase the risk of aspiration.[141][142]

失智症的患者可能会有进食困难的问题,若在可行的情形下,比较建议针对进食困难的患者,有照顾者可以协助进食[111]。针对无法有效吞咽的患者,另一个可行的作法是用胃造口灌食来供给营养。不过若在吸入性肺炎及死亡风险较低的情形下,考虑患者的舒适以及维持其机能状态,协助进食的效果至少和胃造口灌食的效果相当[111][135]。胃管灌食比较容易出现躁动,需要比较多的物理性及化学性约束,也比较容易让褥疮恶化。灌食比较容易造成流体过载、腹泻、腹痛、局部并发症、人际互动减少以及增加误吸入肺部的风险[136][137]

Benefits in those with advanced dementia has not been shown.[143] The risks of using tube feeding include agitation, rejection by the person (pulling out the tube, or otherwise physical or chemical immobilization to prevent them from doing this), or developing pressure ulcers.[116] The procedure is directly related to a 1% fatality rate[144] with a 3% major complication rate.[145] The percentage of people at end of life with dementia using feeding tubes in the US has dropped from 12% in 2000 to 6% as of 2014.[146][147]

针对晚度失智症的患者,还不确定这些作法是否有助益[138]。胃管灌食的风险是容易躁动、患者会拒绝(将管子拔出,会需要用其他物理或化学的限制方式让患者不去拔管子)、也会造成褥疮[111]。此程序和1%的死亡率[139]以及3%的的并发重症比较有关[140]。在美国失智症患者在临终时仍使用胃管灌食的比例,从2000年的12%降到2014年的6%[141][142]。

饮食

编辑In those with celiac disease or non-celiac gluten sensitivity, a strict gluten-free diet may relieve the symptoms given a mild cognitive impairment.[46][47] Once dementia is advanced no evidence suggests that a gluten free diet is useful.[46]

针对乳糜泻或是非乳糜泻麸质敏感的轻度认知失调的患者,无麸质饮食可能可以缓解其症状[42][43]。若发展到失智症,目前还没有证据支持无麸质饮食的效果[42]。

替代疗法

编辑Aromatherapy and massage have unclear evidence.[148][149] Studies support the efficacy and safety of cannabinoids in relieving behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia.[150]

芳香疗法及按摩在失智症上的疗效,相关的证据还不清楚[143][144]。研究支持用大麻素缓解失智症行为及心理症状的效果及安全性[145]。

Omega-3 fatty acid supplements from plants or fish sources do not appear to benefit or harm people with mild to moderate Alzheimer's disease. It is unclear whether taking omega-3 fatty acid supplements can improve other types of dementia.[151]

对于轻度到中度的阿兹海默症患者,来自植物或是鱼的Ω-3脂肪酸补充品似乎对患者没有帮助,不过也没有损害。目前还不清楚Ω-3脂肪酸补充品对其他种类的失智症是否有帮助[146]。

和缓治疗

编辑Given the progressive and terminal nature of dementia, palliative care can be helpful to patients and their caregivers by helping people with the disorder and their caregivers understand what to expect, deal with loss of physical and mental abilities, support the person's wishes and goals including surrogate decision making, and discuss wishes for or against CPR and life support.[152][153] Because the decline can be rapid, and because most people prefer to allow the person with dementia to make their own decisions, palliative care involvement before the late stages of dementia is recommended.[154][155] Further research is required to determine the appropriate palliative care interventions and how well they help people with advanced dementia.[156]

由于失智症病程进展以及终末不可逆的特质,和缓医疗可以帮助患者以及照顾者,让他们理解接下来可能发生事,处理生理以及心智机能的丧失、支持患者的期望以及目标(包括一些妥协性的决策),以及讨论在有生命危急时,希不希望进行CPR及生命支持[147][148]。因为失智症的机能退化很快,大部份的人都希望患者是自己进行这个决定,因此和缓医疗建议在失智症的最后一个病程之前就要进行[149][150]。有关如何决定适当的和缓医疗方式,以及针对末期病患的助益如何,都还需要更多的资料支持[157]。 (by Wolfch)

Person-centered care helps maintain the dignity of people with dementia.[158]

患者中心医疗可以让失智症的患者仍可以维持其尊严[152]。(by Wolfch)

流行病学

编辑 <100 100–120 120–140 140–160 160–180 180–200 | 200–220 220–240 240–260 260–280 280–300 >300 |

The number of cases of dementia worldwide in 2010 was estimated at 35.6 million.[159] In 2015, 46.8 million people live with dementia, with 58% living in low and middle income countries.[160] The prevalence of dementia differs in different world regions, ranging from 4.7% in Central Europe to 8.7% in North Africa/Middle East; the prevalence in other regions is estimated to be between 5.6 and 7.6%.[160] The number of people living with dementia is estimated to double every 20 years. In 2013 dementia resulted in about 1.7 million deaths, up from 0.8 million in 1990.[26] Around two-thirds of individuals with dementia live in low- and middle-income countries, where the sharpest increases in numbers were predicted in a 2009 study.[159]

2010年,世界上的失智症患者计约3560万人[149]。到2015年,患有失智症的人数约有4680万,其中 58% 的患者生活于中低收入国家[150]。失智症的盛行率随世界及区域而有所不同,中欧约4.7%,北非和中东则约8.7%[150]。失智症的案例数约每20年会翻倍。到2013年,失智症导致的死亡案例已从1990年的80万上升到约170万例[23]。其中三分之二的案例居住于中低收入户国家,且这些区域的案例数增长幅度也最为剧烈[149]。

The annual incidence of dementia diagnosis is over 9.9 million worldwide. Almost half of new dementia cases occur in Asia, followed by Europe (25%), the Americas (18%) and Africa (8%). The incidence of dementia increases exponentially with age, doubling with every 6.3 year increase in age.[160] Dementia affects 5% of the population older than 65 and 20–40% of those older than 85.[161] Rates are slightly higher in women than men at ages 65 and greater.[161]

全球每年约会增加990万例。其中约有一半的新诊断案例位于亚洲,其馀多到少分别为欧洲(25%)、美洲(18%),和非洲(8%)。失智症的发生率会随年龄呈指数性是增长,约每6.3年即会上升一倍[150]。65以上的年长者约有5%人口为失智症所苦,85岁以上的长者则高达20-40%[151]。其中在65岁以上的年长者中,女性发生比率较男性略高[151]。

(这边incidence 不用发生率一词是因为该句呈现的并非一个比率)

Dementia impacts not only individuals with dementia, but also their carers and the wider society. Among people aged 60 years and over, dementia is ranked the 9th most burdensome condition according to the 2010 Global Burden of Disease (GBD) estimates. The global costs of dementia was around US$818 billion in 2015, a 35.4% increase from US$604 billion in 2010.[160]

失智症除了影响患者本身之外,对于照护者和整个社会也会造成负担。根据2010年全球疾病负担研究(Global Burden of Disease,GBD)显示,对于60岁以上的长者而言,失智症在所有疾病中造成的负担为第九名。2010年,失智症约耗费全球6040亿美金,2015年这个数字则上升至8180亿,上升了35.4%[150]。

历史

编辑Until the end of the 19th century, dementia was a much broader clinical concept. It included mental illness and any type of psychosocial incapacity, including reversible conditions.[162] Dementia at this time simply referred to anyone who had lost the ability to reason, and was applied equally to psychosis, "organic" diseases like syphilis that destroy the brain, and to the dementia associated with old age, which was attributed to "hardening of the arteries".

在十九世纪之前,在医学临床上,失智是范围较广的概念,包括了心理疾病,也包括了社会心理机能丧失的症状,(可逆的症状也包括在内)[157]。这个时期“失智”指的就是失去理解能力的人,以及精神病,或是一些会破坏大脑的生理疾病(例如梅毒),其中也包括了老年时会产生的失智,当时认为的原因是“动脉硬化”。

Dementia has been referred to in medical texts since antiquity. One of the earliest known allusions to dementia is attributed to the 7th-century BC Greek philosopher Pythagoras, who divided the human lifespan into six distinct phases: 0–6 (infancy), 7–21 (adolescence), 22–49 (young adulthood), 50–62 (middle age), 63–79 (old age), and 80–death (advanced age). The last two he described as the "senium", a period of mental and physical decay, and that the final phase was when "the scene of mortal existence closes after a great length of time that very fortunately, few of the human species arrive at, where the mind is reduced to the imbecility of the first epoch of infancy".[163] In 550 BC, the Athenian statesman and poet Solon argued that the terms of a man's will might be invalidated if he exhibited loss of judgement due to advanced age. Chinese medical texts made allusions to the condition as well, and the characters for "dementia" translate literally to "foolish old person".[来源请求]

从古代史开始,医学文献中就有失智症的记载。目前有关失智症最早的典故是出自西元前第七世纪古希腊哲学的毕达哥拉斯,他将人生分为六个不同的阶段:0-6岁(儿童)、7-21岁(青少年)、22-49岁(青壮年)、50-62岁(中年)、63-79岁(老年)以及80岁以后(advanced age)。他将最后二段描述为“衰老期”,是心智以及身体都退化的阶段,最后一段则是“生命在一段长久的时间后会走到尽头,届时心智也会退化到如初生时的失能状态。幸运的是,只有极少数的人会活到这么久。”[158]。在西元前550年时,雅典的政治家及诗人梭伦就认为,若一个人因为年老而失去判断能力,则他的遗嘱条款应该要失效。中医学也有描述类似失智的症状[来源请求]。而以往也曾用“老年痴呆症”来作为Dementia的翻译。

Athenians Aristotle and Plato spoke of the mental decay of advanced age, apparently viewing it as an inevitable process that affected all old men, and which nothing could prevent. Plato stated that the elderly were unsuited for any position of responsibility because, "There is not much acumen of the mind that once carried them in their youth, those characteristics one would call judgement, imagination, power of reasoning, and memory. They see them gradually blunted by deterioration and can hardly fulfill their function."[来源请求]

雅典的亚里士多德及柏拉图曾提到老年时的心智衰退,将这些症状视为是会影响所有老年人,不可逆的过程。柏拉图曾认为老年人不适合担任任何职务,因为“年轻时曾有的敏锐头脑,判断力、想像力、理解力及记忆力,在年老时已所剩无几。这些机能慢慢的退化及恶化,很难再发挥作用。”[来源请求]

For comparison, the Roman statesman Cicero held a view much more in line with modern-day medical wisdom that loss of mental function was not inevitable in the elderly and "affected only those old men who were weak-willed". He spoke of how those who remained mentally active and eager to learn new things could stave off dementia. However, Cicero's views on aging, although progressive, were largely ignored in a world that would be dominated for centuries by Aristotle's medical writings. Physicians during the Roman Empire, such as Galen and Celsus, simply repeated the beliefs of Aristotle while adding few new contributions to medical knowledge.

比较起来,罗马政治家西塞罗的观点比较接近现代医学的观点,认为老年人的心智退化是可逆的,而且“只影响那些意志薄弱的老年人”h。他提出精神仍然活跃而且热切学习新事物的人不容易患有失智症。不过西塞罗有关老年的理论虽然先进,但当时是以亚里士多德的医学思想为主,因此西塞罗的理论被忽视了。罗马帝国时的医学家,例如盖伦及克理索主要是重复亚里士多德的理论,偶尔才会加入新的医学知识。

Byzantine physicians sometimes wrote of dementia. It is recorded that at least seven emperors whose lifespans exceeded 70 years displayed signs of cognitive decline. In Constantinople, special hospitals housed those diagnosed with dementia or insanity, but these did not apply to the emperors, who were above the law and whose health conditions could not be publicly acknowledged.

拜占庭帝国的医师曾写到失智症。有记录提到至少有七位70岁以上的皇帝出现认知衰退的情形。君士坦丁堡有特殊的医院诊断失智症或是精神错乱,但这不适用于皇帝,其地位比法律还要高,而其健康状态也不会公开,

Otherwise, little is recorded about dementia in Western medical texts for nearly 1700 years. One of the few references was the 13th-century friar Roger Bacon, who viewed old age as divine punishment for original sin. Although he repeated existing Aristotelian beliefs that dementia was inevitable, he did make the progressive assertion that the brain was the center of memory and thought rather than the heart.

此外,在西方的医学文献中,有长达1700年的时间只有少许有关失智症的记录。其中一个资料是来自13世纪的男修道士罗吉尔·培根,他认为老年因为原罪而有的惩罚。虽然他重复亚里士多德失智症不可逆的论点,不过提出了一个进步的想法,认为心不是记忆的中心,大脑才是。

Poets, playwrights, and other writers made frequent allusions to the loss of mental function in old age. William Shakespeare notably mentions it in plays such as Hamlet and King Lear.

诗人、剧作家以及其他作家常会描述到老年时的心智功能退化。像威廉·莎士比亚的《哈姆雷特》及《李尔王》中都有描述。

During the 19th century, doctors generally came to believe that elderly dementia was the result of cerebral atherosclerosis, although opinions fluctuated between the idea that it was due to blockage of the major arteries supplying the brain or small strokes within the vessels of the cerebral cortex.

在十九世纪时,医师普遍认为老年的失智是因为脑动脉粥样硬化的结果,不过是因为脑中大动脉的阻塞,或因为大脑皮质中小血管造成的小型中风,则没有定论。

In 1907 Alzheimer's disease was described. This was associated with particular microscopic changes in the brain, but was seen as a rare disease of middle age because the first person diagnosed with it was a 50-year-old woman. By 1913–20, schizophrenia had been well-defined in a way similar to later times.

1907年时开始有阿兹海默症的描述,其症状和大脑特别的微观变化有关,不过因为一开始是在五十岁的女性身上发现,被视为是罕见的中年疾病。大约在1913年至1920年时,也开始有精神分裂症的定义,定义方式和现在的差不多。

This viewpoint remained conventional medical wisdom through the first half of the 20th century, but by the 1960s it was increasingly challenged as the link between neurodegenerative diseases and age-related cognitive decline was established. By the 1970s, the medical community maintained that vascular dementia was rarer than previously thought and Alzheimer's disease caused the vast majority of old age mental impairments. More recently however, it is believed that dementia is often a mixture of conditions.

在20世纪的前半段时,有关失智的观点仍停留在传统的医学智慧。1960年代开始建立神经退化障碍以及老年认知退化之间的关联,传统的医学智慧也开始受到挑战。1970年代时,医学界认为血管型失智比以往认为的比例要少,老年心智退化主要是因为阿兹海默症的影响。之后又慢慢有新的观点,认为失智症是几种病症所混合而成。

In 1976, neurologist Robert Katzmann suggested a link between senile dementia and Alzheimer's disease.[164] Katzmann suggested that much of the senile dementia occurring (by definition) after the age of 65, was pathologically identical with Alzheimer's disease occurring in people under age 65 and therefore should not be treated differently.[165] Katzmann thus suggested that Alzheimer's disease, if taken to occur over age 65, is actually common, not rare, and was the fourth- or 5th-leading cause of death, even though rarely reported on death certificates in 1976.

神经学家罗伯特·卡兹曼在1976年提出老年失智症和阿兹海默症的关联性[159],卡兹曼认为(依照其定义)发生在65岁以上的老年失智症,和许多65岁以下发生的阿兹海默症,在病理上是相同的,因此需视为同一种疾病[160]。因此卡兹曼推测:若将阿兹海默症的条件放宽到65岁以上,此疾病其实相当常见,是死因中的第四名到第五名,只是很少出现在1976年的死因鉴定书。

A helpful finding was that although the incidence of Alzheimer's disease increased with age (from 5–10% of 75-year-olds to as many as 40–50% of 90-year-olds), no threshold was found by which age all persons developed it. This is shown by documented supercentenarians (people living to 110 or more) who experienced no substantial cognitive impairment. Some evidence suggests that dementia is most likely to develop between ages 80 and 84 and individuals who pass that point without being affected have a lower chance of developing it. Women account for a larger percentage of dementia cases than men, although this can be attributed to their longer overall lifespan and greater odds of attaining an age where the condition is likely to occur.[来源请求]

另一个对诊断有帮助的发现是:虽然阿兹海默症的发生率会随年龄增加而提高(从75岁的5-10%到90岁的40-50%),但没有证据显示超过某一年龄就一定会罹患阿兹海默症,例如有资料记录超过110岁的人瑞,没有出现明显的认知退化。有些证据支持发生阿兹海默症的年龄主要是在80至84岁,超过此一阶段后,发生率会下降。女性罹患失智症的比例比男性要高,不过不确定是不是因为女性平均寿命较高,会活到容易罹患阿兹海默症的年龄有关[来源请求]。

Much like other diseases associated with aging, dementia was comparatively rare before the 20th century, because few people lived past 80. Conversely, syphilitic dementia was widespread in the developed world until it was largely eradicated by the use of penicillin after World War II. With significant increases in life expectancy thereafter, the number of people over 65 started rapidly climbing. While elderly persons constituted an average of 3–5% of the population prior to 1945, by 2010 many countries reached 10–14% and in Germany and Japan, this figure exceeded 20%. Public awareness of Alzheimer's Disease greatly increased in 1994 when former US president Ronald Reagan announced that he had been diagnosed with the condition.

失智症和其他和老年有关的疾病类似,在20世纪之前很少出现,因为当时很少人可以活到80岁。以前梅毒失智症在已开发国家很普遍,后来因为青霉素的使用,此病症在第二次世界大战后已经绝迹。随著预期生命的显著增加,65岁以上的人口也快速增加。在1945年以前,老年人约占总人口的3-5%,在2010年时会占约10-14%,若是德国及日本,会占到20%以上。1994年时前美国总统罗纳德·里根宣布他罹患阿兹海默症,也提升大众对阿兹海默症的认识。

In the 21st century, other types of dementia were differentiated from Alzheimer's disease and vascular dementias (the most common types). This differentiation is on the basis of pathological examination of brain tissues, by symptomatology, and by different patterns of brain metabolic activity in nuclear medical imaging tests such as SPECT and PETscans of the brain. The various forms have differing prognoses and differing epidemiologic risk factors. The causal etiology of many of them, including Alzheimer's disease, remains unclear.[来源请求]

21世纪时,除了阿兹海默症及血管型失智症外,也分别出Frontotemporal dementia,其差异以在脑部组织的病理学检查、症状学为基础,而在核医学成像测试(例如SPECT及正子断层照影)下,大脑代谢活动的模式也有所不同。这些差异造成了不同的预后,以及不同的流行病学危险因素。失智症中有许多种的确切原因还不清楚,其中也包括了阿兹海默症[来源请求]。

辞汇

编辑Dementia in the elderly was once called senile dementia or senility, and viewed as a normal and somewhat inevitable aspect of growing old. This terminology is no longer standard.[166][167]

老年时的失智症曾被称为是“老年失智症”(senile dementia),视为是年老时正常的现象,在一定程度上是无法避免的。此词语已不是医学标准的用法[161][162]。

By 1913–20 the term dementia praecox was introduced to suggest the development of senile-type dementia at a younger age. Eventually the two terms fused, so that until 1952 physicians used the terms dementia praecox (precocious dementia) and schizophrenia interchangeably. The term precocious dementia for a mental illness suggested that a type of mental illness like schizophrenia (including paranoia and decreased cognitive capacity) could be expected to arrive normally in all persons with greater age (see paraphrenia). After about 1920, the beginning use of dementia for what is now understood as schizophrenia and senile dementia helped limit the word's meaning to "permanent, irreversible mental deterioration". This began the change to the later use of the term.

在1913年至1920年间,出现了早发型失智症词语,说明老年型失智症在较年轻时的情形。最后二个词融合了,在1952年之前,医生会将“早发型失智症”及“思觉失调症”(schizophrenia)视为是同义词,彼此替换使用。精神疾病上的“早发型失智症”意味著有一种类似思觉失调症(包括偏执以及认知能力减退)的症状,只要年龄够大,都自然而然会出现。在1920年后,开始使用“失智症”来描述后来认为是“思觉失调症”的症状,而“老年失智症”是专指永久性、不可逆的心智退化。这是此一词语后来意义变化的开始。

The view that dementia must always be the result of a particular disease process led for a time to the proposed diagnosis of "senile dementia of the Alzheimer's type" (SDAT) in persons over the age of 65, with "Alzheimer's disease" diagnosed in persons younger than 65 who had the same pathology. Eventually, however, it was agreed that the age limit was artificial, and that Alzheimer's disease was the appropriate term for persons with that particular brain pathology, regardless of age.

以往认为失智症一定是某一种特别疾病所导致的后果,这也造成了有一段时间会将65岁以上的患者诊断为“阿兹海默型老年性失智”(SDAT),将65岁以下有相关症状的患者诊断为“阿兹海默症”。后来专家们同意年龄的限制是人为不必要的,针对这种脑部病变,不论年龄为何,最适合的诊断即为“阿兹海默症”。

After 1952 mental illnesses including schizophrenia were removed from the category of organic brain syndromes, and thus (by definition) removed from possible causes of "dementing illnesses" (dementias). At the same, however, the traditional cause of senile dementia – "hardening of the arteries" – now returned as a set of dementias of vascular cause (small strokes). These were now termed multi-infarct dementias or vascular dementias.

在1952年后,包括思觉失调症在内的精神疾病已不再列在器质性脑症候群的分类中,因此(依照定义),思觉失调症也就不再是失智症的可能病因。同时,老年型失智症的传统原因“血管硬化”变成一种血管型的失智症(小型中风),现在会称为“多发性梗塞型失智症”或是“血管型失智症”。

社会及文化

编辑The societal cost of dementia is high, especially for family caregivers.[168]

失智症的社会成本很高,尤其会影响家庭中的照顾者[163]。

Many countries consider the care of people living with dementia a national priority and invest in resources and education to better inform health and social service workers, unpaid caregivers, relatives and members of the wider community. Several countries have authored national plans or strategies.[169][170] These plans recognize that people can live reasonably with dementia for years, as long as the right support and timely access to a diagnosis are available. Former British Prime Minister David Cameron described dementia as a "national crisis", affecting 800,000 people in the United Kingdom.[171]

许多国家将照顾失智症患者列为国家优先事务,投入资源以及教育,让医疗人员、社会服务工作者、无薪看护者、亲属以及社会大众对失智症有更多的了解。不少国家有订定国家级的计划或是战略[164][165]。这些计划认知到,只要提供正确的支援,并且有及时的诊断,人可以在有失智症的情形下生活相当一段时间。前英国首相戴维·卡梅伦称失智症是“国家危机”,在英国影响超过80万人[166]。

There, as with all mental disorders, people with dementia could potentially be a danger to themselves or others, they can be detained under the Mental Health Act 1983 for assessment, care and treatment. This is a last resort, and is usually avoided by people with family or friends who can ensure care.

不过如同所有的精神疾病一样,失智症患者有可能会伤害自身,也可能会伤害他人。依照Mental Health Act 1983可以拘留,以进行评估、照料及治疗。这是最后的手段,只有在失智症患者没有可以照顾他的家人或是朋友时,才会使用此方式处理。

Some hospitals in Britain work to provide enriched and friendlier care. To make the hospital wards calmer and less overwhelming to residents, staff replaced the usual nurses' station with a collection of smaller desks, similar to a reception area. The incorporation of bright lighting helps increase positive mood and allow residents to see more easily.[172]

有些英国的医院会提供较丰富以及较友善的照护。为了让病房更安静,对住院患者的压力较小,工作人员将一般的护理站换成许多较小的桌子,类似接待区。其中也整合了较明亮的灯光让住院患者有较积极的情绪,也让患者可以看的比较清楚[167]。

Driving with dementia can lead to injury or death. Doctors should advise appropriate testing on when to quit driving.[173] The United Kingdom DVLA (Driver & Vehicle Licensing Agency) states that people with dementia who specifically have poor short term memory, disorientation, or lack of insight or judgment are not allowed to drive, and in these instances the DVLA must be informed so that the driving licence can be revoked. They acknowledge that in low-severity cases and those with an early diagnosis, drivers may be permitted to continue driving.

失智症患者驾驶有可能会造成受伤甚至死亡。医师应该针对患者何时要停止驾驶进行相关的测验[168]。英国的DVLA(车辆及驾驶执照机构)提出失智者患者若短期记忆力不佳、失去方向感或判断能力,都不允许驾驶,这些情形都需要知会DVLA,以作废对应的执照。他们也同意针对症状轻或是早期诊断的驾驶,可以继续开车。

Many support networks are available to people with dementia and their families and caregivers. Charitable organisations aim to raise awareness and campaign for the rights of people living with dementia. Support and guidance are available on assessing testamentary capacity in people with dementia.[174]

已针对失智症患者、家庭以及照顾者有许多的支持网路。慈善机构计划开展活动,提升大众对失智症的认知,并且争取和失智症同住者的权益。针对评估失智症遗嘱的效力上,已有相关的支持以及指引[169]。

In 2015, Atlantic Philanthropies announced a $177 million gift aimed at understanding and reducing dementia. The recipient was Global Brain Health Institute, a program co-led by the University of California, San Francisco and Trinity College Dublin. This donation is the largest non-capital grant Atlantic has ever made, and the biggest philanthropic donation in Irish history.[175]

2015年时,大西洋慈善基金会(Atlantic Philanthropies)为了要了解及减少失智症,捐赠了1.77兆美金。得主是全球脑健康研究所(Global Brain Health Institute),是由加利福尼亚大学旧金山分校以及都柏林三一学院合作的计划。此捐赠是大西洋慈善基金会进行过最大笔的非资金捐赠,也是爱尔兰历史上最大规模的的慈善捐赠[169]。

口腔卫生

编辑目前,并没有足够的研究结果能够证明,不佳的口腔健康状况和认知能力的下降有明确的关系。然而,错误的刷牙习惯和常态性的牙龈红肿,已被证实可作为失智症的罹病风险指标[176]。

口腔病原菌

编辑阿兹海默症和牙周炎的关联因素是口腔菌群[177]。口腔中的细菌种类有齿龈假单胞菌(P. gingivalis)、具核梭杆菌(F. nucleatum)、中间普氏菌(P. intermedia)及福赛斯坦纳菌(T. forsythia)。在阿兹海默症患者脑部有发现六种口腔密螺旋体(Trepomena)[178]。螺旋体为嗜神经性(neurotropic)病原体,会伤害神经及造成发炎。炎症性病原体是阿兹海默症的指标,在阿兹海默症患者的脑部有发现和牙周炎有关的细菌[178]。这些细菌会入侵脑部的神经、增加血脑屏障的通透性,促使阿兹海默症的发作。若患者有过多的牙菌斑,有认知能力下降的风险[179]。口腔卫生不良会对语言和营养有不良影响,使得整体健康及认知的衰退。

口腔中的病毒

编辑50岁或是更年长的族群中,有超过70%会检测到单纯疱疹病毒(HSV)。单纯疱疹病毒会持续的维持在周围神经系统,可能因为压力、疾病或疲劳而引发[178]。含有淀粉样蛋白的斑块或是神经原纤维缠结(NFT)中和病毒相关蛋白的比例很高,因此证实了HSV-1参与了阿兹海默症的病理。神经原纤维缠结是阿兹海默症的主要标记物,HSV-1产生了NFT中的主要成份[180]。

参考文献

编辑- ^ Dementia. MedlinePlus. U.S. National Library of Medicine. 14 May 2015 [6 August 2018]. (原始内容存档于12 May 2015).

Dementia Also called: Senility

- ^ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 2.14 引用错误:没有为名为

WHO2014的参考文献提供内容 - ^ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 Burns A, Iliffe S. Dementia. BMJ. February 2009, 338: b75. PMID 19196746. S2CID 220101432. doi:10.1136/bmj.b75.

- ^ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 Dementia. www.who.int. [7 November 2020] (英语).

- ^ 5.0 5.1 Dementia diagnosis and assessment (PDF). pathways.nice.org.uk. [2014-11-30]. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于2014-12-05).

- ^ Hales, Robert E. The American Psychiatric Publishing Textbook of Psychiatry. American Psychiatric Pub. 2008: 311. ISBN 978-1-58562-257-3. (原始内容存档于2017-09-08).

- ^ 引用错误:没有为名为

Lancet2020的参考文献提供内容 - ^ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Kavirajan H, Schneider LS. Efficacy and adverse effects of cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine in vascular dementia: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. The Lancet. Neurology. September 2007, 6 (9): 782–92. PMID 17689146. doi:10.1016/s1474-4422(07)70195-3.

- ^ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 Commission de la transparence. Drugs for Alzheimer's disease: best avoided. No therapeutic advantage [Drugs for Alzheimer's disease: best avoided. No therapeutic advantage]. Prescrire International. June 2012, 21 (128): 150. PMID 22822592.

- ^ Global, regional, and national burden of Alzheimer's disease and other dementias, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol. January 2019, 18 (1): 88–106. PMC 6291454 . PMID 30497964. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30403-4.

- ^ Normal ageing vs dementia. Alzheimer's Society. [22 November 2020] (英语).

- ^ McKeith IG, Ferman TJ, Thomas AJ, et al. Research criteria for the diagnosis of prodromal dementia with Lewy bodies. Neurology (Review). April 2020, 94 (17): 743–55. PMC 7274845 . PMID 32241955. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000009323.

- ^ 13.00 13.01 13.02 13.03 13.04 13.05 13.06 13.07 13.08 13.09 13.10 13.11 13.12 13.13 13.14 13.15 13.16 13.17 13.18 13.19 13.20 13.21 Budson A, Solomon P. Memory loss : a practical guide for clinicians. [Edinburgh?]: Elsevier Saunders. 2011. ISBN 978-1-4160-3597-8.

- ^ 14.0 14.1 Association, American Psychiatric. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders : DSM-5. 5th. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association. 2013: 591–603. ISBN 978-0-89042-554-1.

- ^ Gauthier S. Clinical diagnosis and management of Alzheimer's disease 3rd. Abingdon, Oxon: Informa Healthcare. 2006: 53–54. ISBN 978-0-203-93171-4. (原始内容存档于2016-05-03).

- ^ 16.0 16.1 Loy CT, Schofield PR, Turner AM, Kwok JB. Genetics of dementia. Lancet. March 2014, 383 (9919): 828–40. PMID 23927914. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(13)60630-3.

- ^ Dementia overview (PDF). pathways.nice.org.uk. [2014-11-30]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2014-12-05).

- ^ 18.0 18.1 Birks J. Cholinesterase inhibitors for Alzheimer's disease. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. January 2006, (1): CD005593. PMID 16437532. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005593.

- ^ Rolinski M, Fox C, Maidment I, McShane R. Cholinesterase inhibitors for dementia with Lewy bodies, Parkinson's disease dementia and cognitive impairment in Parkinson's disease (PDF). The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. March 2012, 3 (3): CD006504. PMID 22419314. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006504.pub2.

- ^ 20.0 20.1 Forbes D, Forbes SC, Blake CM, Thiessen EJ, Forbes S. Exercise programs for people with dementia. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (Submitted manuscript). April 2015, 132 (4): 195–96. PMID 25874613. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006489.pub4.

- ^ Information for Healthcare Professionals: Conventional Antipsychotics. fda.gov. 2008-06-16 [2014-11-29]. (原始内容存档于2014-11-29).

- ^ National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Low-dose antipsychotics in people with dementia. nice.org.uk. [2014-11-29]. (原始内容存档于2014-12-05).

- ^ GBD 2015 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet. October 2016, 388 (10053): 1545–1602. PMC 5055577 . PMID 27733282. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31678-6.

- ^ 24.0 24.1 24.2 Larson EB, Yaffe K, Langa KM. New insights into the dementia epidemic. The New England Journal of Medicine. December 2013, 369 (24): 2275–77. PMC 4130738 . PMID 24283198. doi:10.1056/nejmp1311405.

- ^ Umphred, Darcy. Neurological rehabilitation 6th. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Mosby. 2012: 838. ISBN 978-0-323-07586-2. (原始内容存档于2016-04-22).

- ^ 26.0 26.1 GBD 2013 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators. Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet. January 2015, 385 (9963): 117–71. PMC 4340604 . PMID 25530442. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61682-2.

- ^ Dementia – Signs and Symptoms. American Speech Language Hearing Association.

- ^ Şahin Cankurtaran, E. Management of Behavioral and Psychological Symptoms of Dementia.. Noro Psikiyatri Arsivi. December 2014, 51 (4): 303–12. PMC 5353163 . PMID 28360647. doi:10.5152/npa.2014.7405.

- ^ Sight, perception and hallucinations in dementia (PDF). Alzheimer's Society. October 2015 [2015-11-04]. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于2017-08-13).

- ^ Cerejeira J, Lagarto L, Mukaetova-Ladinska EB. Behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. Frontiers in Neurology. 2012, 3: 73. PMC 3345875 . PMID 22586419. doi:10.3389/fneur.2012.00073.

- ^ Calleo J, Stanley M. Anxiety Disorders in Later Life Differentiated Diagnosis and Treatment Strategies. Psychiatric Times. 2008, 25 (8). (原始内容存档于2009-09-04).

- ^ Geddes J, Gelder MG, Mayou R. Psychiatry. Oxford [Oxfordshire]: Oxford University Press. 2005: 141. ISBN 978-0-19-852863-0. OCLC 56348037.

- ^ Shub D, Kunik ME. Psychiatric Comorbidity in Persons With Dementia: Assessment and Treatment Strategies. Psychiatric Times. 2009-04-16, 26 (4). (原始内容存档于2009-04-27).

- ^ 34.0 34.1 Hugo J, Ganguli M. Dementia and cognitive impairment: epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Clinics in Geriatric Medicine. August 2014, 30 (3): 421–42. PMC 4104432 . PMID 25037289. doi:10.1016/j.cger.2014.04.001.

- ^ Jenkins, Catharine. Dementia care at a glance. Ginesi, Laura; Keenan, Bernie. Chichester, West Sussex. 2016-01-26. ISBN 978-1-118-85998-8. OCLC 905089525.

- ^ Rohrer JD, Knight WD, Warren JE, Fox NC, Rossor MN, Warren JD. Word-finding difficulty: a clinical analysis of the progressive aphasias. Brain. January 2008, 131 (Pt 1): 8–38. PMC 2373641 . PMID 17947337. doi:10.1093/brain/awm251.

- ^ Islam, Maheen; Mazumder, Mridul; Schwabe-Warf, Derek; Stephan, Yannick; Sutin, Angelina R.; Terracciano, Antonio. Personality Changes With Dementia From the Informant Perspective: New Data and Meta-Analysis. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2019-02-01, 20 (2): 131–137. ISSN 1525-8610. PMID 30630729. doi:10.1016/j.jamda.2018.11.004 (英语).

- ^ Erickson K. How We Die Now: Intimacy and the Work of Dying. Temple University Press. 2013-09-27: 109–11. ISBN 978-1-4399-0823-5. (原始内容存档于2016-12-23).

- ^ Dawes, P. Hearing interventions to prevent dementia.. HNO. March 2019, 67 (3): 165–171. PMC 6399173 . PMID 30767054. doi:10.1007/s00106-019-0617-7.

- ^ 40.0 40.1 40.2 40.3 Thomson, RS; Auduong, P; Miller, AT; Gurgel, RK. Hearing loss as a risk factor for dementia: A systematic review.. Laryngoscope Investigative Otolaryngology. April 2017, 2 (2): 69–79. PMC 5527366 . PMID 28894825. doi:10.1002/lio2.65.

- ^ Hussain M, Berger M, Eckenhoff RG, Seitz DP. General anesthetic and the risk of dementia in elderly patients: current insights. Clinical Interventions in Aging. 2014, 9: 1619–28. PMC 4181446 . PMID 25284995. doi:10.2147/CIA.S49680.

- ^ 42.0 42.1 Iadecola C. The pathobiology of vascular dementia. Neuron. November 2013, 80 (4): 844–66. PMC 3842016 . PMID 24267647. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2013.10.008.

- ^ Finger, Elizabeth C. Frontotemporal Dementias. Continuum (Minneapolis, Minn.). April 2016, 22 (2 Dementia): 464–489. ISSN 1538-6899. PMC 5390934 . PMID 27042904. doi:10.1212/CON.0000000000000300.

- ^ Schofield P. Dementia associated with toxic causes and autoimmune disease. International Psychogeriatrics (Review). 2005,. 17 Suppl 1: S129–47. PMID 16240488. doi:10.1017/s1041610205001997.

- ^ 45.0 45.1 Rosenbloom MH, Smith S, Akdal G, Geschwind MD. Immunologically mediated dementias. Current Neurology and Neuroscience Reports (Review). September 2009, 9 (5): 359–67. PMC 2832614 . PMID 19664365. doi:10.1007/s11910-009-0053-2.

- ^ 46.0 46.1 46.2 46.3 46.4 Zis P, Hadjivassiliou M. Treatment of Neurological Manifestations of Gluten Sensitivity and Coeliac Disease.. Curr Treat Options Neurol (Review). 2019-02-26, 21 (3): 10. PMID 30806821. doi:10.1007/s11940-019-0552-7.

- ^ 47.0 47.1 47.2 Makhlouf S, Messelmani M, Zaouali J, Mrissa R. Cognitive impairment in celiac disease and non-celiac gluten sensitivity: review of literature on the main cognitive impairments, the imaging and the effect of gluten free diet.. Acta Neurol Belg (Review). 2018, 118 (1): 21–27. PMID 29247390. doi:10.1007/s13760-017-0870-z.

- ^ Aarsland D, Kurz MW. The epidemiology of dementia associated with Parkinson disease. Journal of the Neurological Sciences (Review). February 2010, 289 (1–2): 18–22. PMID 19733364. doi:10.1016/j.jns.2009.08.034.

- ^ Galvin JE, Pollack J, Morris JC. Clinical phenotype of Parkinson disease dementia. Neurology. November 2006, 67 (9): 1605–11. PMID 17101891. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000242630.52203.8f.

- ^ Abbasi, Jennifer. Debate Sparks Over LATE, a Recently Recognized Dementia. JAMA. 2019-08-21, 322 (10): 914. doi:10.1001/jama.2019.12232.

- ^ Lamont P. Cognitive Decline in a Young Adult with Pre-Existent Developmental Delay – What the Adult Neurologist Needs to Know. Practical Neurology. 2004, 4 (2): 70–87. doi:10.1111/j.1474-7766.2004.02-206.x. (原始内容存档于2008-10-07).

- ^ Langa KM, Levine DA. The diagnosis and management of mild cognitive impairment: a clinical review. JAMA. December 2014, 312 (23): 2551–61. PMC 4269302 . PMID 25514304. doi:10.1001/jama.2014.13806.

- ^ Neuropathology Group. Medical Research Council Cognitive Function and Aging Study. Pathological correlates of late-onset dementia in a multicentre, community-based population in England and Wales. Neuropathology Group of the Medical Research Council Cognitive Function and Ageing Study (MRC CFAS). Lancet. January 2001, 357 (9251): 169–75. PMID 11213093. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(00)03589-3.

- ^ Wakisaka Y, Furuta A, Tanizaki Y, Kiyohara Y, Iida M, Iwaki T. Age-associated prevalence and risk factors of Lewy body pathology in a general population: the Hisayama study. Acta Neuropathologica. October 2003, 106 (4): 374–82. PMID 12904992. doi:10.1007/s00401-003-0750-x.

- ^ White L, Petrovitch H, Hardman J, Nelson J, Davis DG, Ross GW, et al. Cerebrovascular pathology and dementia in autopsied Honolulu-Asia Aging Study participants. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. November 2002, 977 (9): 9–23. Bibcode:2002NYASA.977....9W. PMID 12480729. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb04794.x.

- ^ Ratnavalli E, Brayne C, Dawson K, Hodges JR. The prevalence of frontotemporal dementia. Neurology. June 2002, 58 (11): 1615–21. PMID 12058088. doi:10.1212/WNL.58.11.1615.

- ^ McKee AC, Cantu RC, Nowinski CJ, Hedley-Whyte ET, Gavett BE, Budson AE, Santini VE, Lee HS, Kubilus CA, Stern RA. Chronic traumatic encephalopathy in athletes: progressive tauopathy after repetitive head injury. Journal of Neuropathology and Experimental Neurology. July 2009, 68 (7): 709–35. PMC 2945234 . PMID 19535999. doi:10.1097/NEN.0b013e3181a9d503.